Computational modelling of literary characters

Luca Giovannini / Daniil Skorinkin

Digital Humanities Network, University of Potsdam

@ FAU Erlangen-Nürnberg, 27 January 2025

ToC

This presentation: plu.sh/cmcerlangen

Characters in

(Computational)

Literary Studies

A personage in a narrative or dramatic work.

(Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms = Baldick 2008)

Character is a text- or media-based figure in a storyworld, usually human or human-like.

(Living Handbook of Narratology = Jannidis 2019)

What is a character, again?

- "Tragedy is the imitation of an action; and an action implies personal agents, who necessarily possess certain distinctive qualities both of character and thought" (Poet. 1449b 35-)

- "tragedy is not a representation of men but of a piece of action, of life, of happiness and unhappiness, which come under the head of action, and the end aimed at is the representation not of qualities of character but of some action (Poet. 1450a 1-)

-

"Without action there cannot be a tragedy; there may be without character-study" (1450a 15-) = "All action is performed by agents, but not all action stems from character" (Rhineland 2000: 531)

- In English, 'characters' indicates both the dramatis personae and the quality of their mind; Aristotle instead distinguishes between agents (πράττοντες) and their character (ἤθη), which is one of the six parts of tragedy he individuates

Back to basics: Aristotle

Formalist & structuralist approaches to character

For a broader overview: Hartner 2024

The character emerges as a result of the narrative shaping of the material and serves, on the one hand, as a means of stringing together the motifs, and on the other hand, as an embodied and personified rationale for the connections between the motifs.

(Boris Tomashevskiy, Theory of literature, 1999 (1925), p. 133)

Formalist approach: characters are merely means of binding plot motives together

We have only recently moved away from a type of criticism that involves discussing (and condemning) the characters of a novel as if they were real people <...> There is no static character, only the dynamic character. And the mere sign of a character, the name of a character, is sufficient for us to avoid scrutinizing the character themselves in every specific instance.

(Yury Tynyanov, The problem of verse language (1924), pp. 8-9)

Tynyanov: characters are names or "signs" in the text that accumulate meanings, not real people

"We occasionally speak of Sarrasine as though he existed, as though he had a future, an unconscious, a soul; however, what we are talking about is his figure (an impersonal network of symbols combined under the proper name “Sarrasine”), not his person (a moral freedom endowed with motives and an overdetermination of meanings): we are developing connotations, not pursuing investigations; we are not searching for the truth of Sarrasine, but for the systematics of a (transitory) site of the text: we mark this site (under the name Sarrasine) so it will take its place among the alibis of the narrative operation, in the indeterminable network of meanings, in the plurality of the codes".

(Roland Barthes, S/Z (1974), p. 94)

Barthes: characters are variable names to mark text segments and associated meanings

The literary character is, essentially, a series of successive appearances of the same figure within the confines of a given text. Over the course of a single text, the character may manifest in a variety of forms: mentions of them in the speech of other characters, the author’s or narrator’s account of events related to the character, analysis of their personality, depictions of their experiences, thoughts, speech, appearance, scenes in which they participate through words, gestures, actions, and so on. The mechanism of the gradual accumulation of these manifestations is particularly evident in large novels with a significant number of characters.

(Lidiya Ginzburg, On literary character (1979), p. 89)

L. Ginzburg (a post-formalist): characters are

text <spans> which gradually accumulate features

- Character as a sequence of instances in the text (motivates markup)

- Character as a marker for text span (c.f. studies of characters as word2vec vectors)

- Character as a dynamic variable that accumulates features (motivates network analysis! among other things)

Takeaway: formalism & structuralism provide some backing for what DH does with characters

- Panel at DH Montreal 2017 (Piper, Algee-Hewitt, Sinha, Ruths, Vala)

- Other examples: Grayson et al. 2016 (characters as word embeddings), Bamman et al., 2014; Yoder et al., 2021 (extraction of character info) Bullard & Alm 2014 (sociolinguistic profiling of characters), Ciotti 2016 (developing an ontology for characters), Piper 2018 (chapter 5)

-

More recently: MITE project (Make it explicit: Documenting interpretations of literary fictions with conceptual formal models, @ CNR/Rome Sapienza/Macerata)

-

Special Issue of Humanities: "The Interpretation of Fictional Characters in Literary Texts: History of Literary Criticism, Philosophy and Formal Ontologies"

-

Characters in DH research

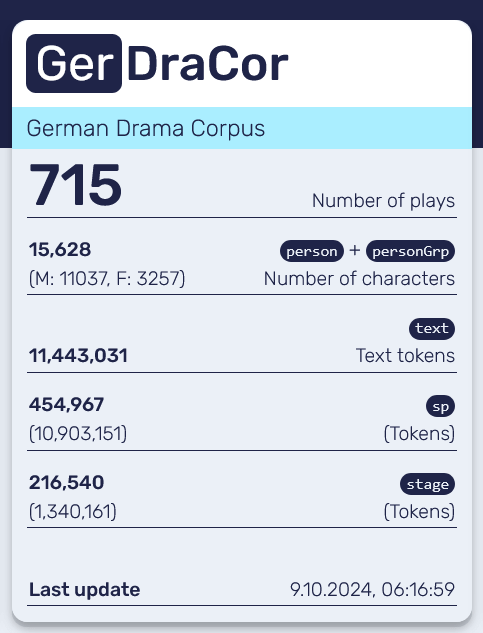

Characters in DraCor

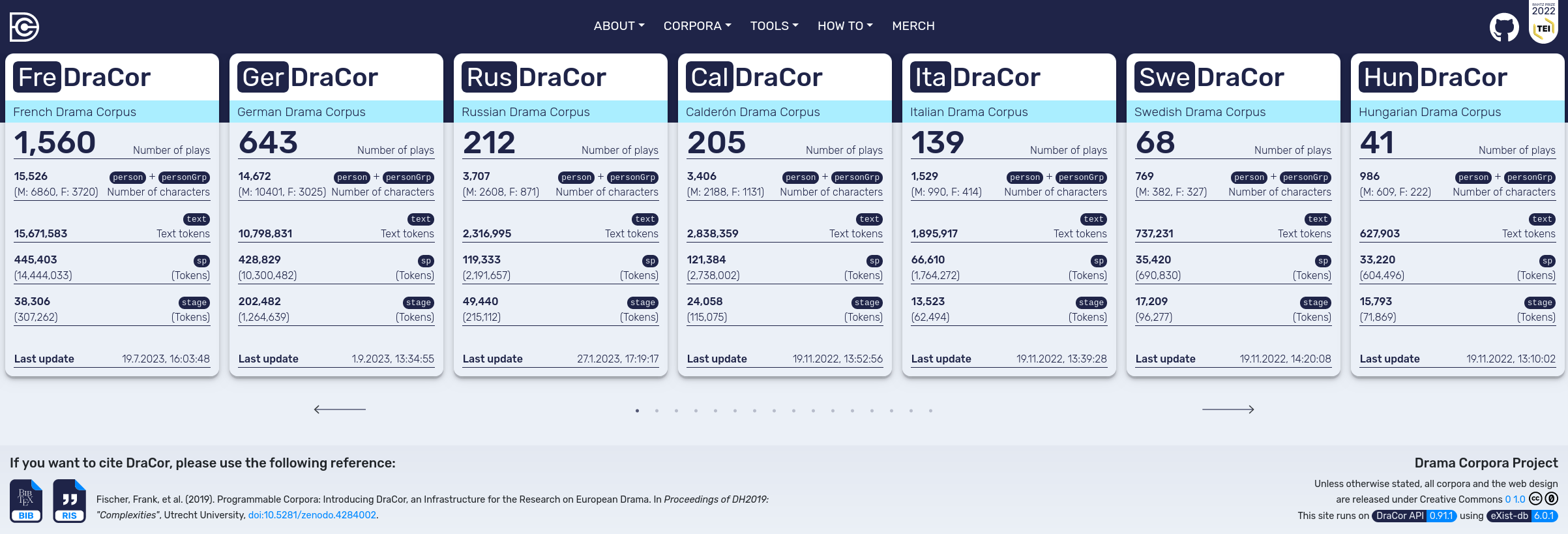

Introducing DraCor

- open platform and network of resources for hosting, accessing, and analysing theatre plays

- +4000 TEI/XML-encoded texts in 15 languages

- a wide range of applications and tools for CLS research (including API wrappers)

- Funded through the CLS INFRA program

- Extended intro: bit.ly/dra106

Introducing DraCor

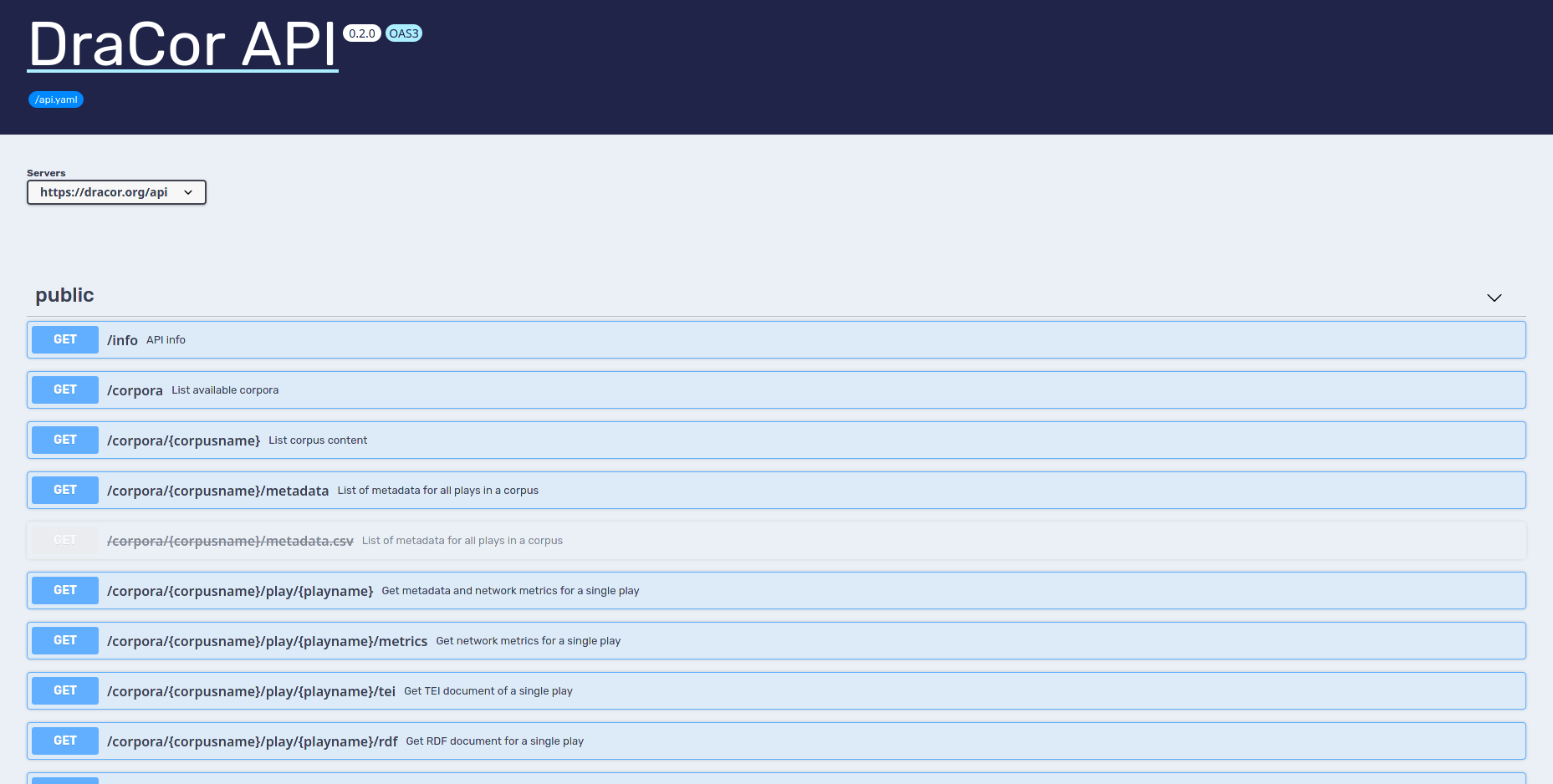

An API (Application Programming Interface) is a set of rules and protocols that allows different software applications to communicate and exchange data or functionality.

DraCor API

Some examples of what you can get through the DraCor API

- We run API calls to get all metrics related to characters for each of the DraCor corpora:

- Time taken: more than 3 hours!

- Script failures:

- Karl Kraus' Last Days of Mankind. Why, you ask?

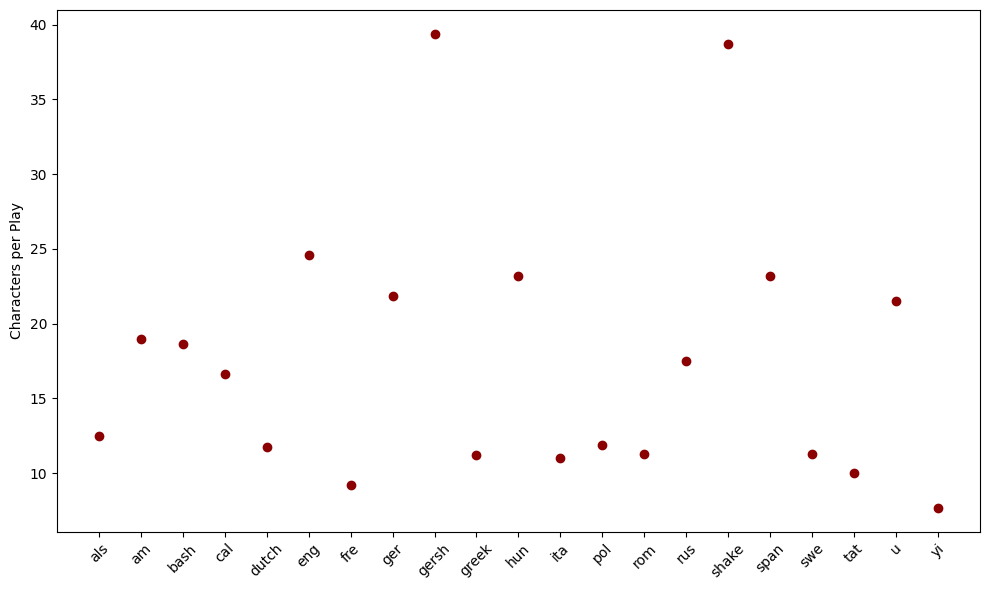

What we did

unique characters

63431

plays

4281

Mean number of characters per play

across DraCor corpora

-

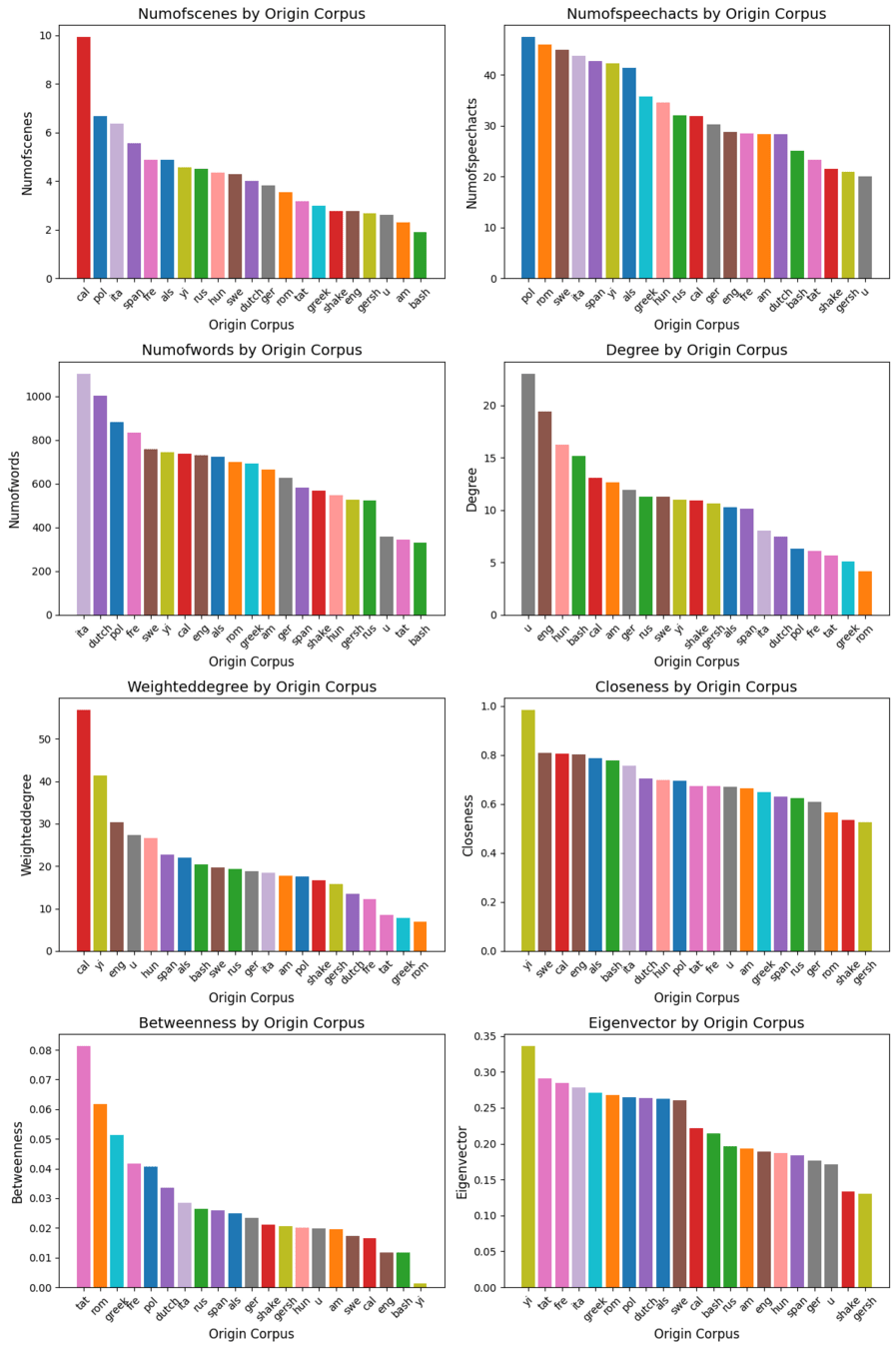

numOfScenes

-

numOfSpeechActs (<p></p> or <l></l>)

-

numOfWords

SPEECH

- degree

- weightedDegree

- closeness

- betweenness

- eigenvector

NETWORK

Metrics

Describing character centrality

| scenes, speech acts, words | general verbal prominence of a character (how much stage/speaking time he has) |

| degree | connections to other characters |

| weighted degree | connections adjusted by frequency/intensity |

| closeness | having the shortest distance from others |

| betweenness | acting as a bridge between other figures |

| eigenvector | connections to other highly connected figures |

What about the similarities betwen characters in different corpora?

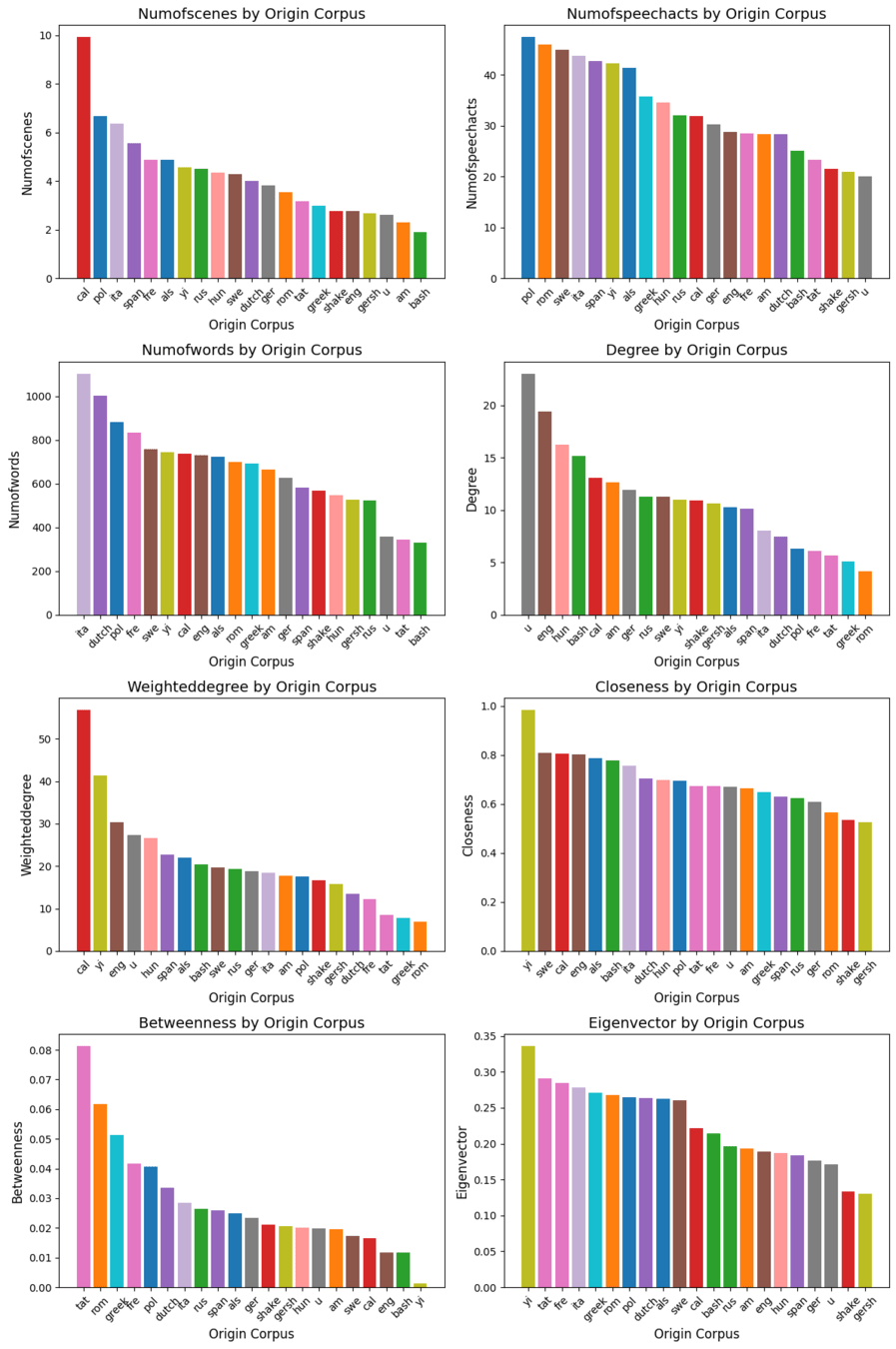

Mean values for each metric by corpus

(1/2)

Mean values for each metric by corpus

(2/2)

Let's do some exploratory data analysis

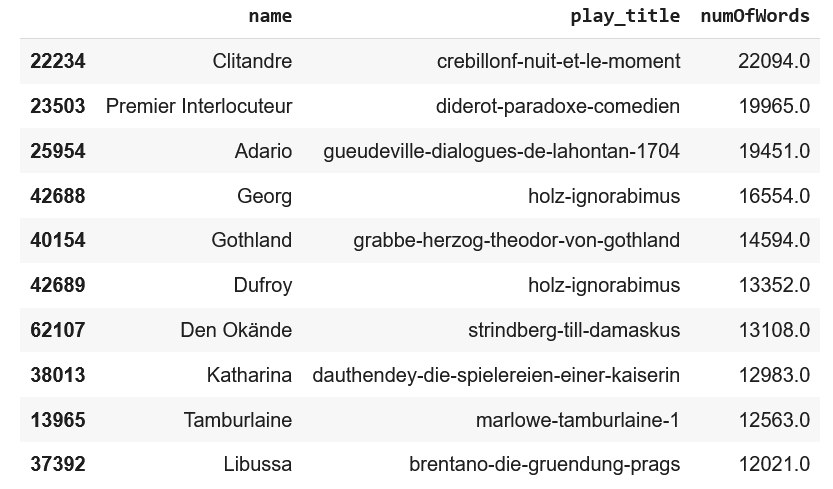

The biggest chatterboxes of world literature

Some DraCor archeology: https://dlina.github.io/The-Biggest-Chatterbox-in-German-Literature (2015)

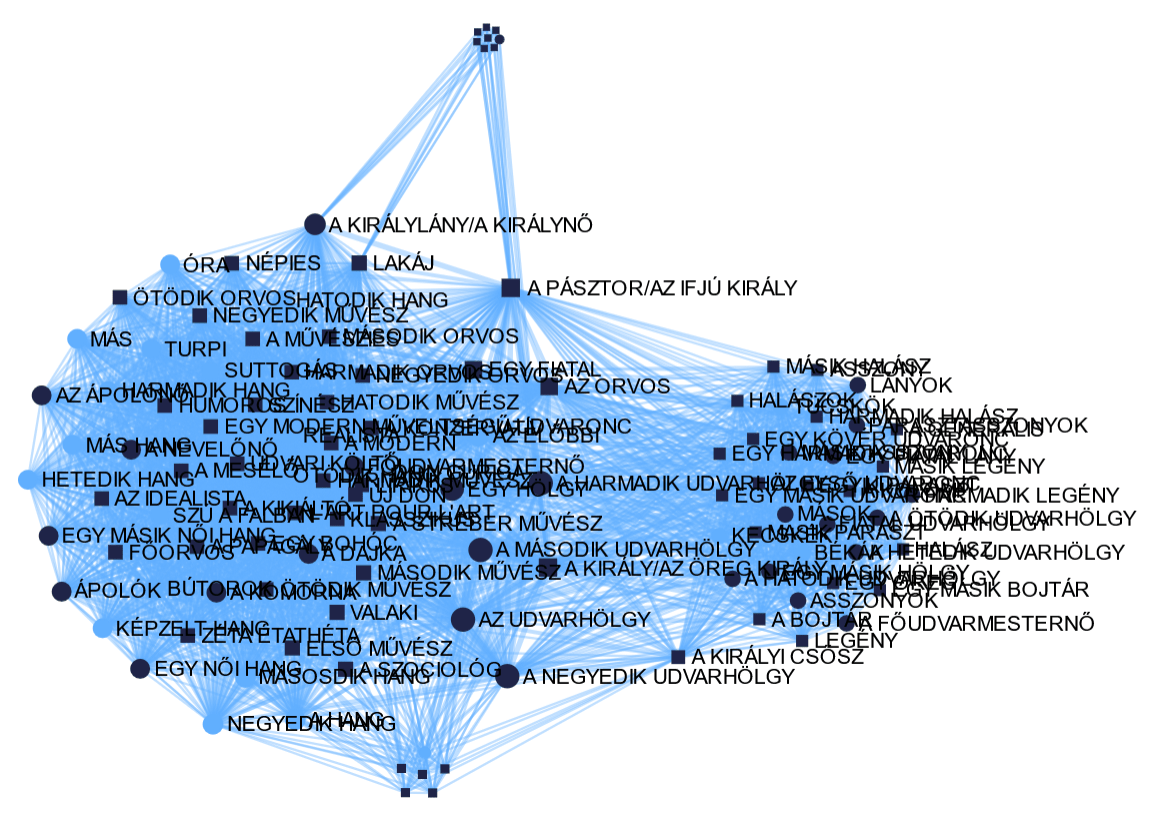

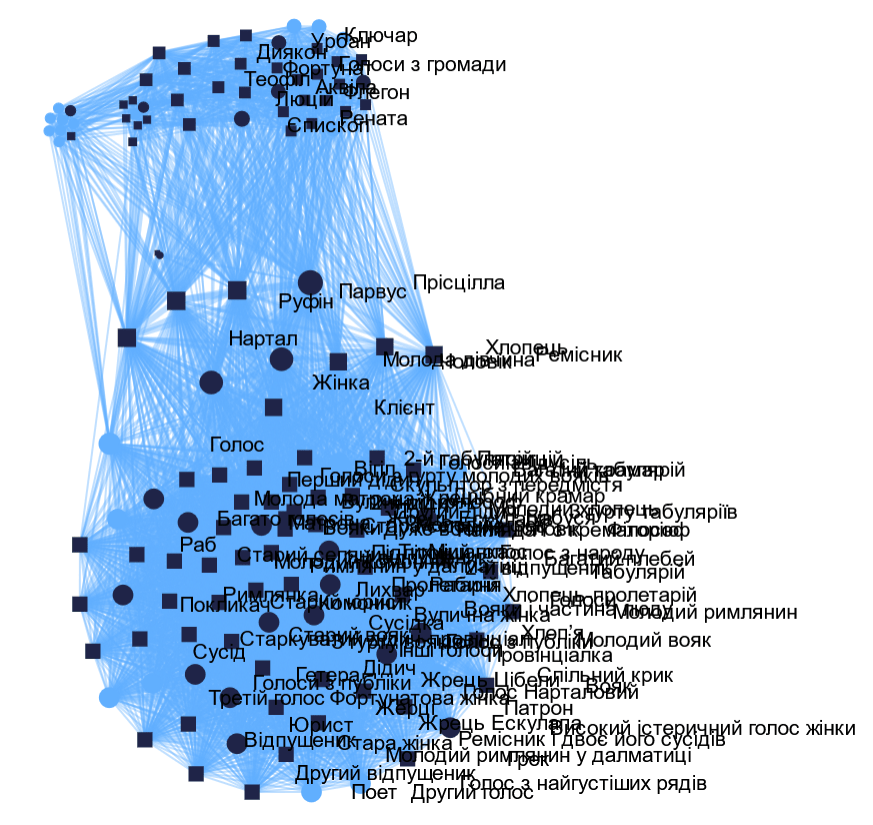

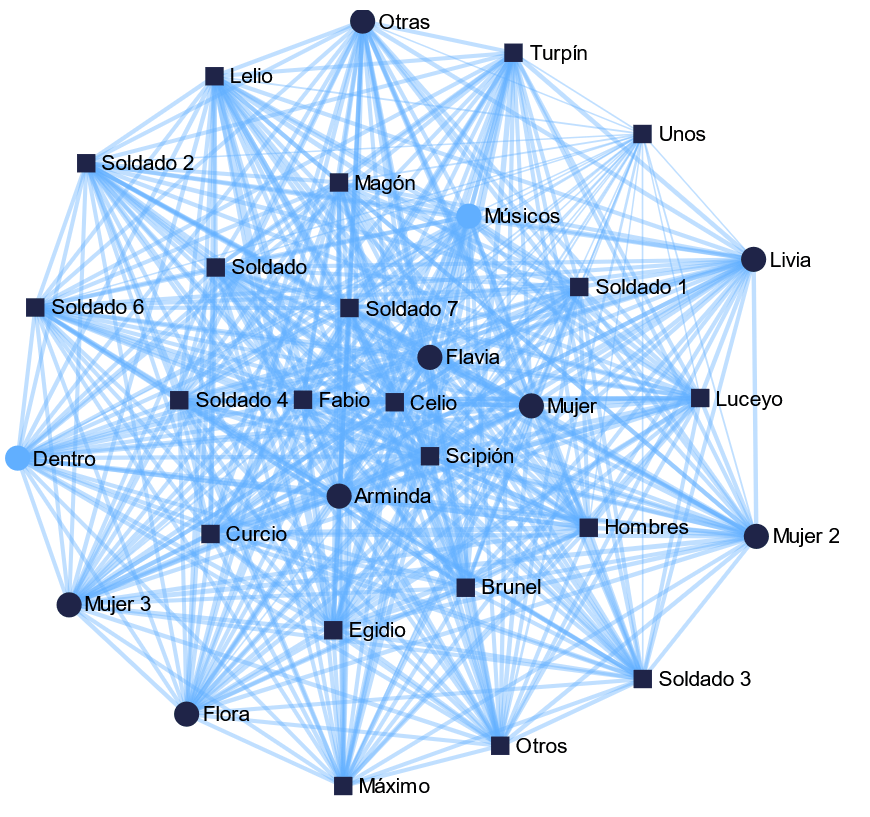

Hyperconnected

All first 17 characters with the highest degree come either from Lesya Ukrainka's Rufin and Priscilla (🇺🇦) or from Mihály Babits' The Second Song (🇭🇺). Why? Take a look:

-

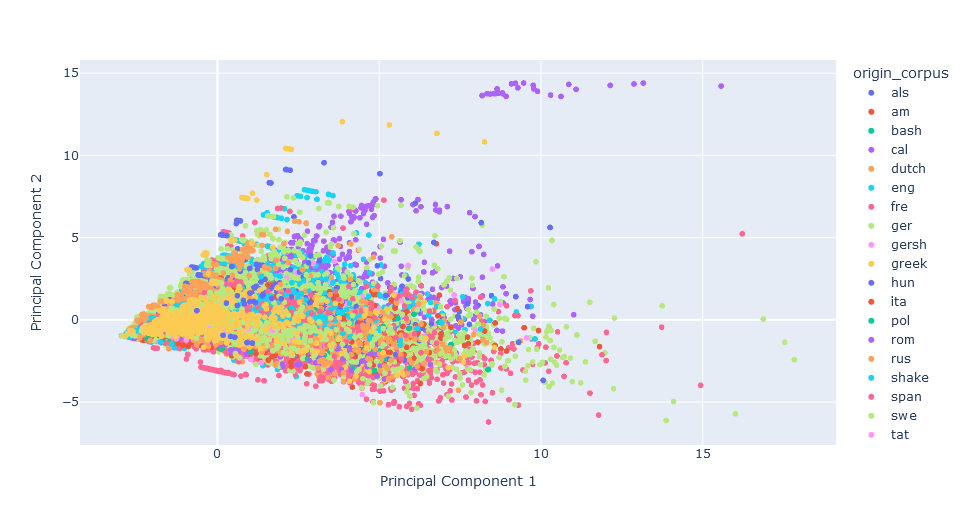

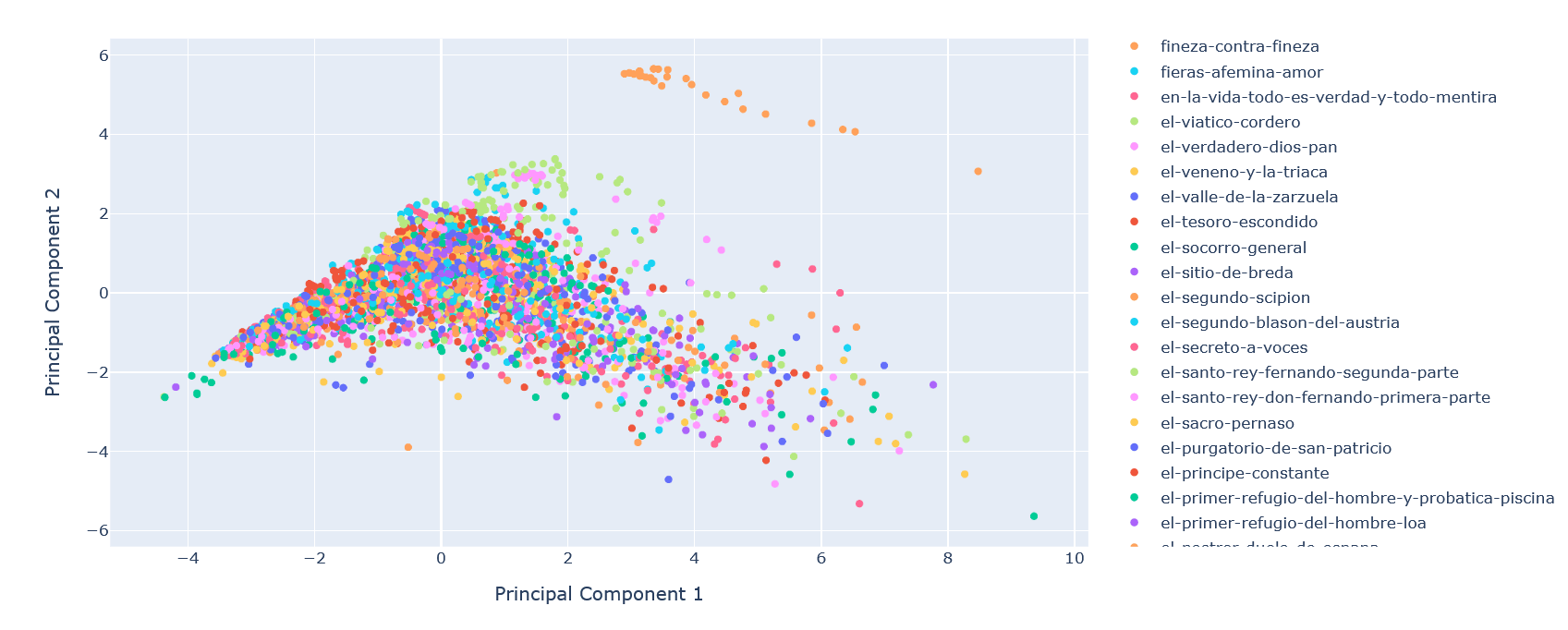

Using vectorisation as an hermeneutic tool

-

vectors are ordered list of numbers

-

step 1: constructing a vector out of some play metrics

-

step 2: comparing vectors to gain insights into the plays' formal properties → vector distance as a proxy for some type of formal distance between texts (cf. Giovannini 2025)

-

Testing an holistic approach to metric visualisation

Simple PCA, all 8 metrics

Calderonian anomaly

El segundo Scipión

(1676)

Segments: 101

All-in at segment 2 (at 2%)

Network size: 31

Density: 1

Diameter: 1

Average path length: 1

Average clustering coefficient: 1

Average degree: 30

Maximum degree: 30 (31 characters)

...real peculiarities or result of encoding choices (e.g. scene division)?

Focus: GerDraCor

In terms of speech acts and word counts, many characters from Arno Holz' Naturalist drama Ignorabimus are prominent...

...but, in terms of scene presence, the clear winner is Nestroy' Das Haus der Temperamente (1837) -- a Posse where the action takes place at the same time in four apartments in the same building!

Stage prominence

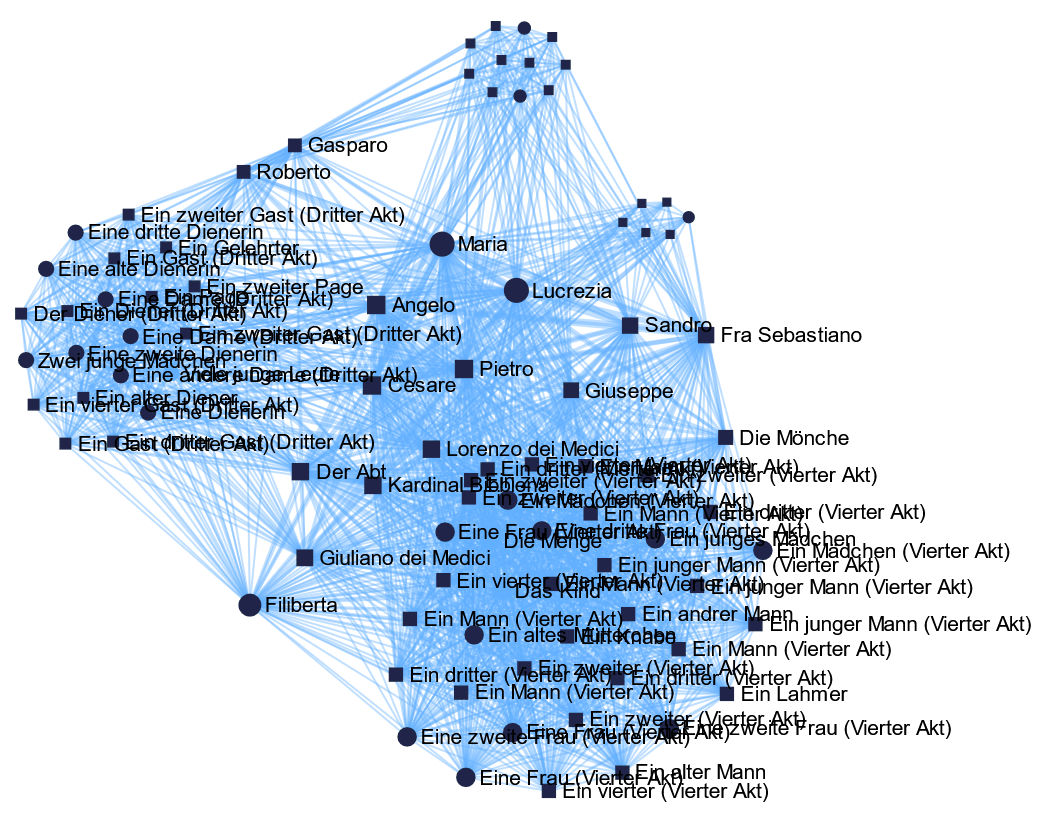

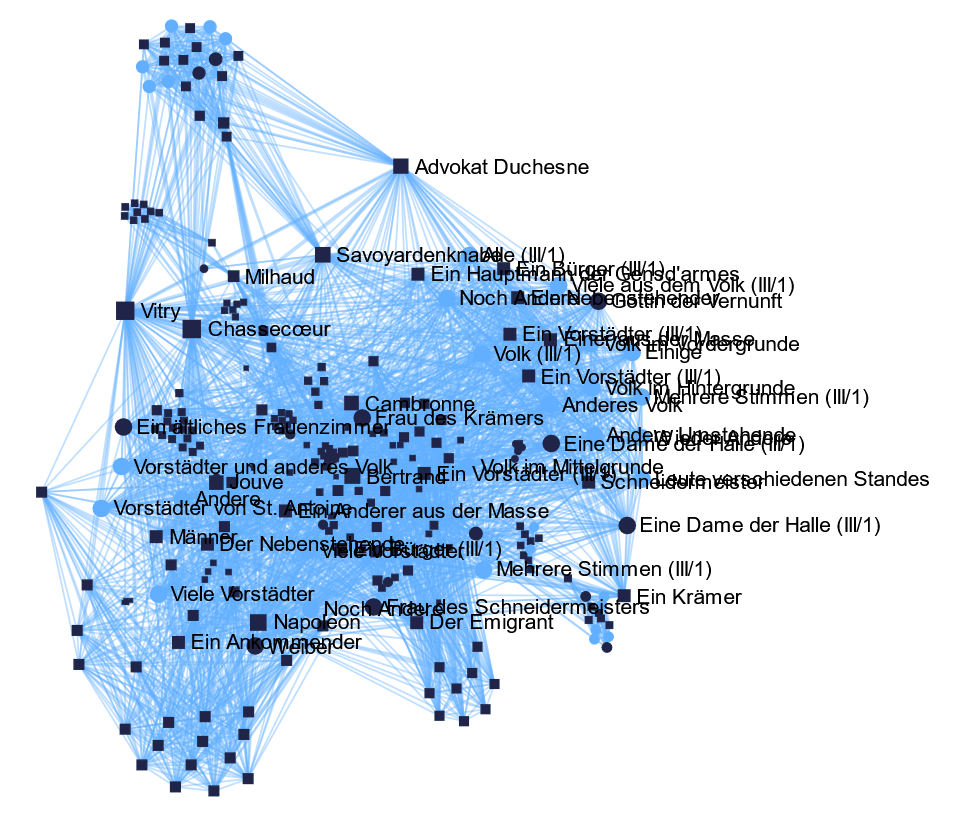

The most connected characters are those playing key roles in broad historical plays...

Lily Braun, Mutter Maria (1913)

Christian Grabbe, Napoleon oder Die Hundert Tage (1831)

👑Vitry/Chassecoeur (106)

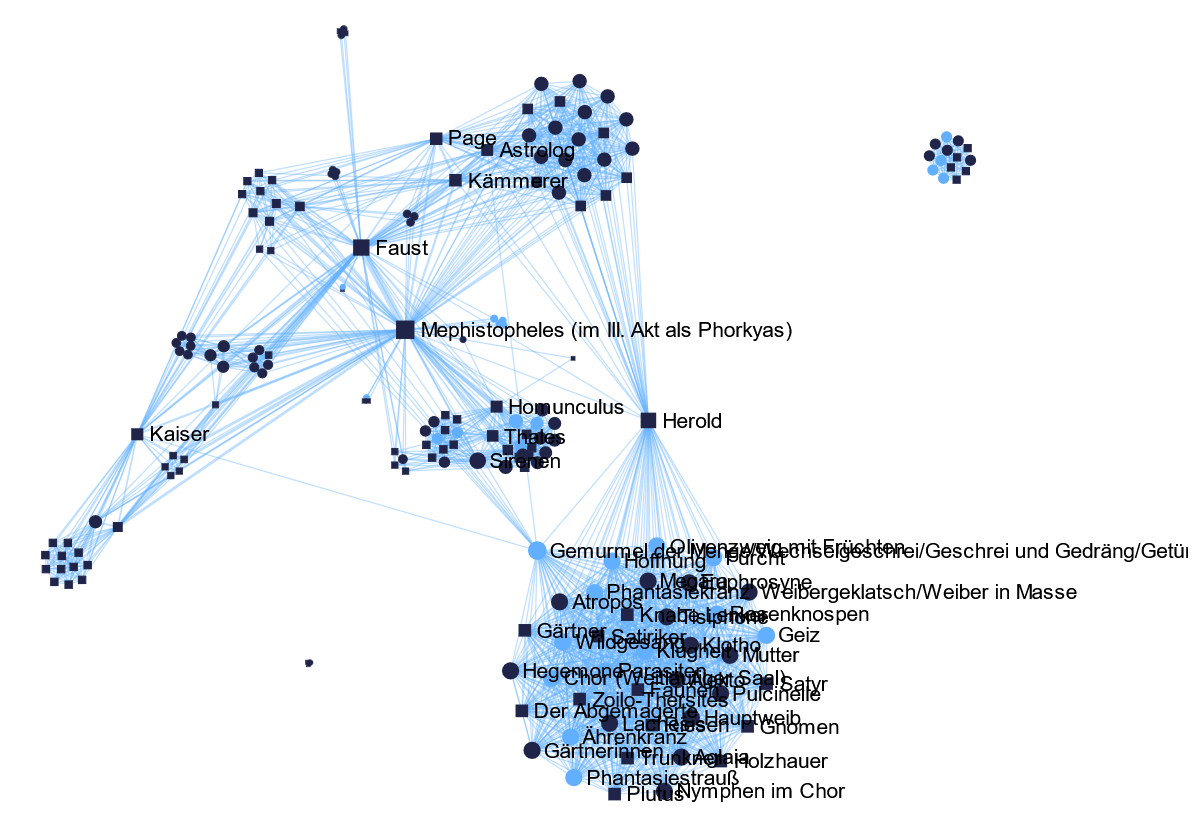

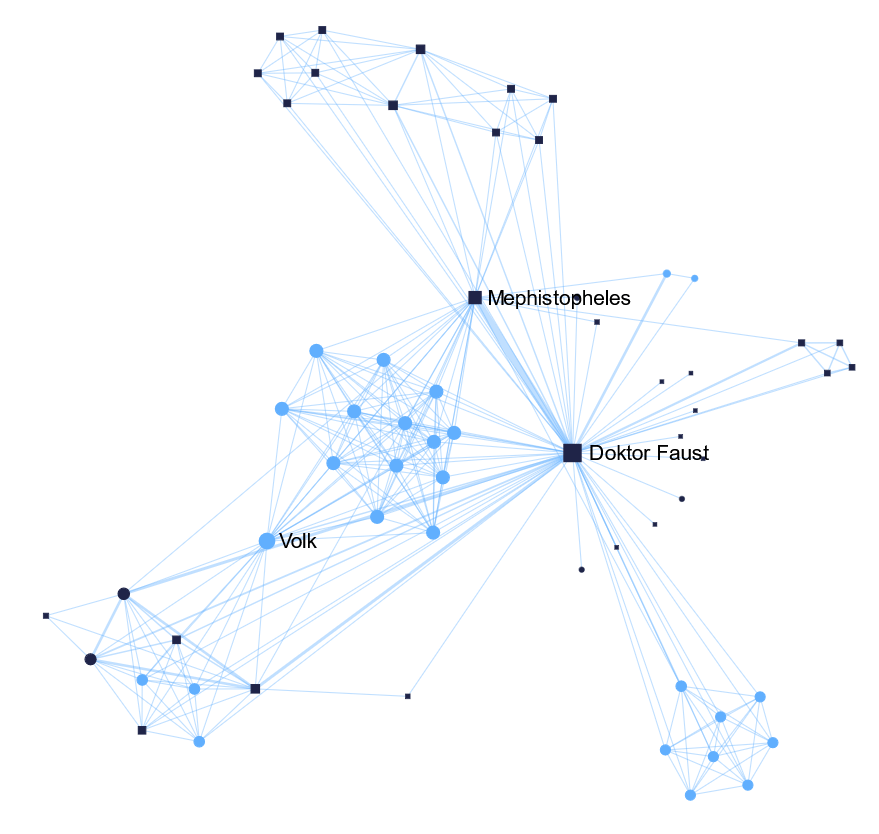

J. W. Goethe, Faust II (1832) → Mephistopheles

...this stays true even if we take into account the intensity of connections (WG)

Clemens Brentano, Die Gründung Prags. Ein historisch-romantisches Drama (1814)

Betweenness: tying narratives together

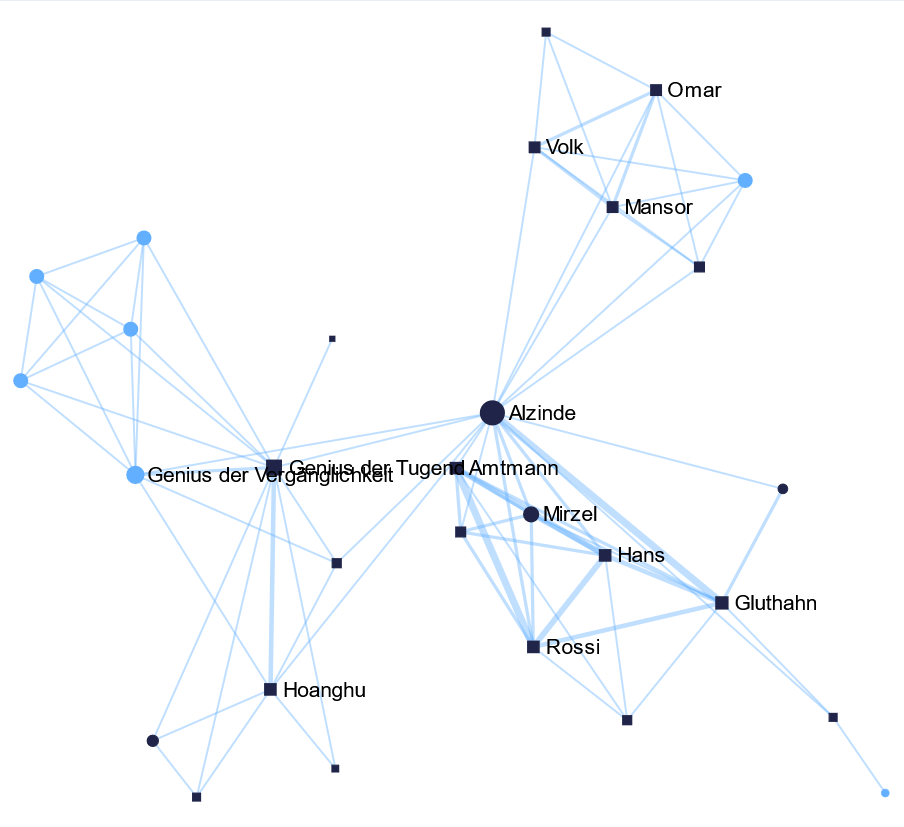

Ferdinand Raimund, Moisasurs Zauberfluch (1827)

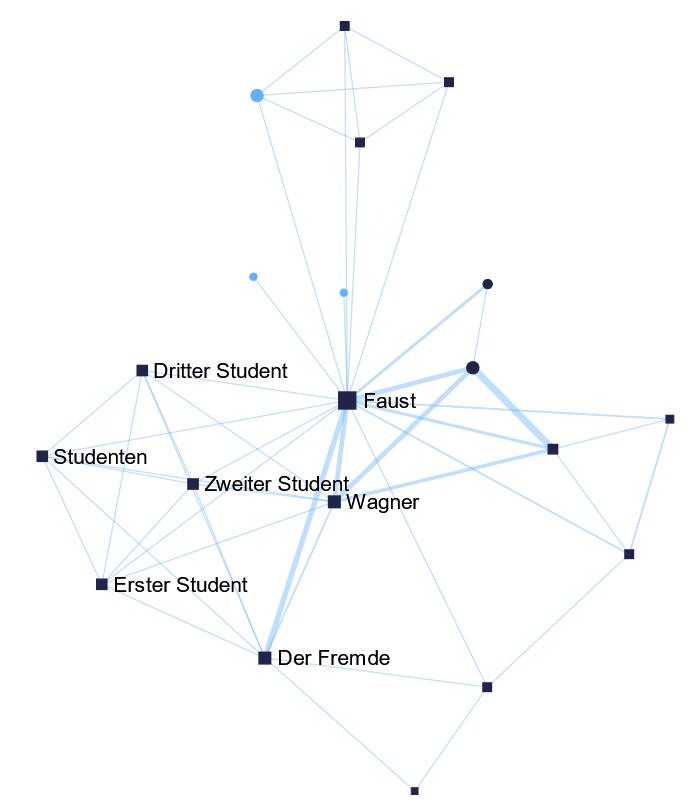

August Klingemann, Faust (1812)

Julius von Soden, Doktor Faust (1797)

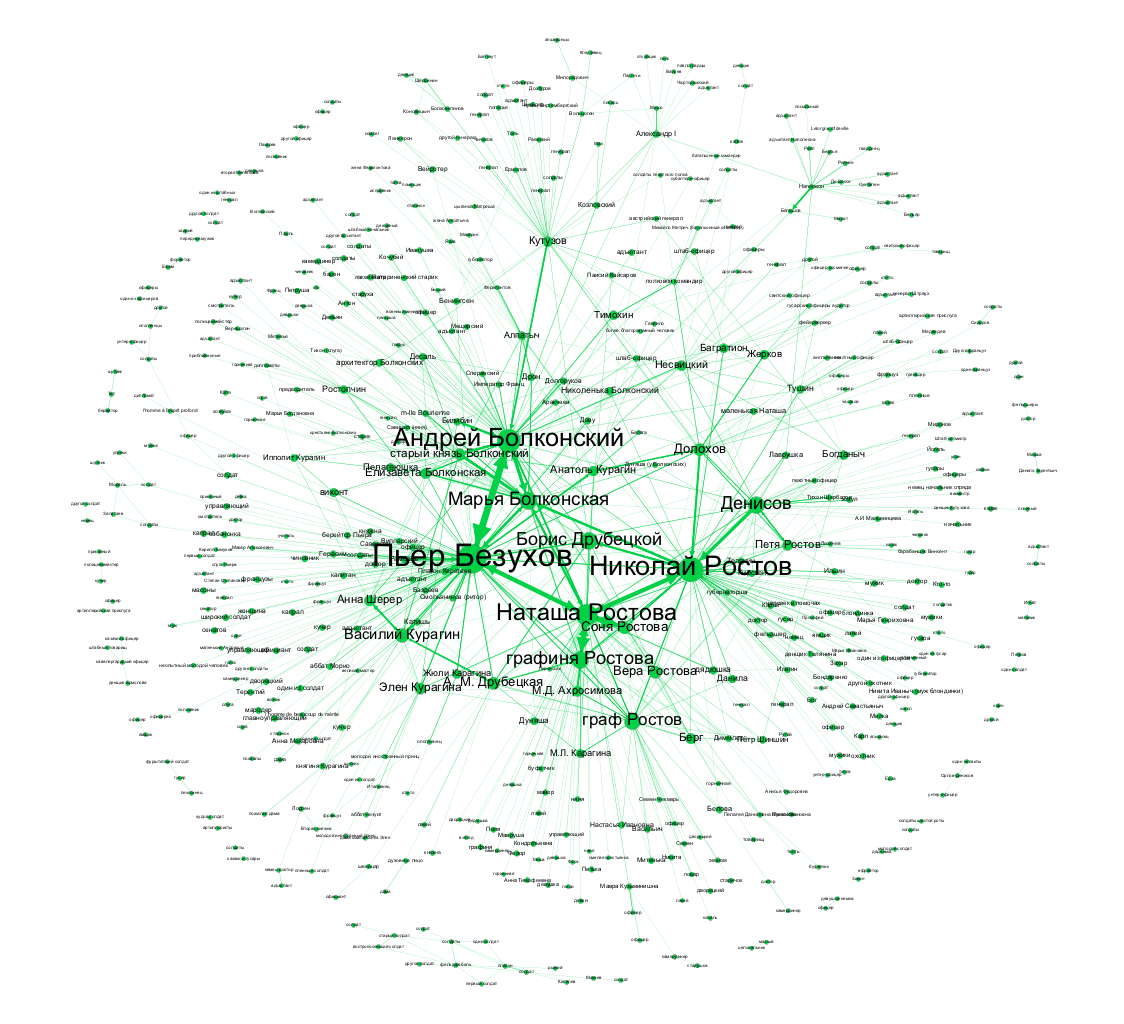

Characters in Tolstoy's War and Peace

- Mentions of characters (including anaphoric ones)

- Character speech

- Case roles (agent, object, experiencer, possessor — along the lines of Fillmore 1967)

- Simplified version available at: doi.org/10.31860/openlit-2022.1-C005

Basis: TEI markup of War and Peace

The mechanism of the gradual accumulation of these manifestations is particularly evident in large novels with a significant number of characters.

(Lidiya Ginzburg, On literary character (1979), p. 89)

Motivation: Lidiya Ginzburg, once again

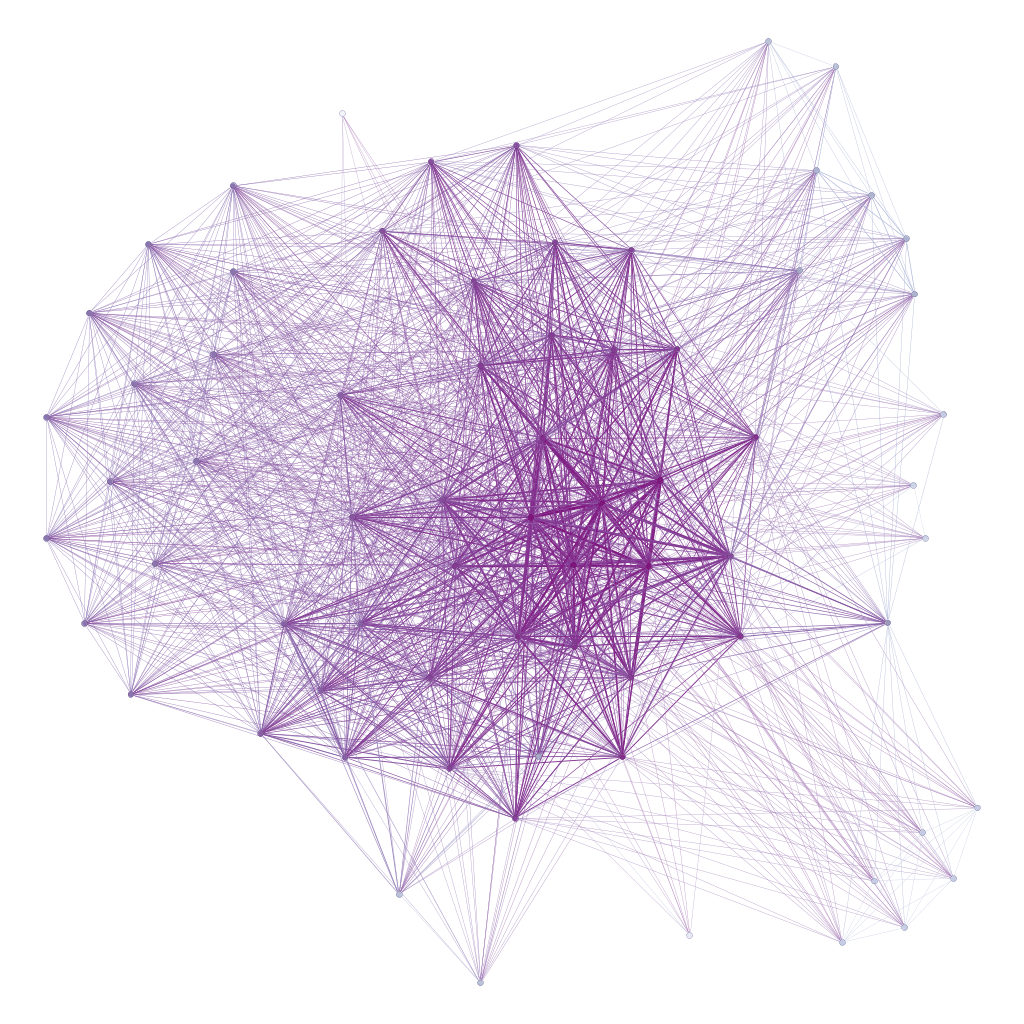

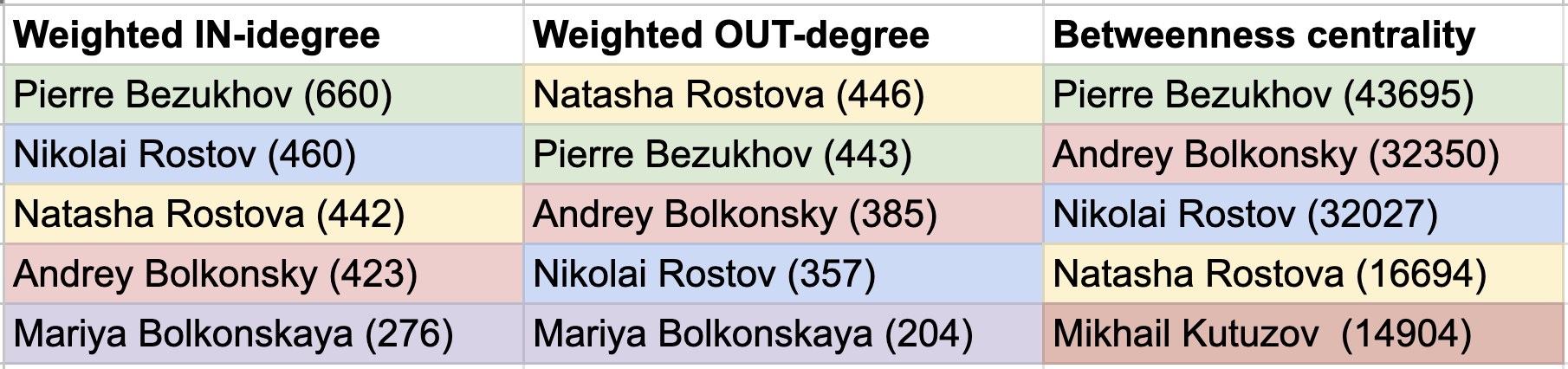

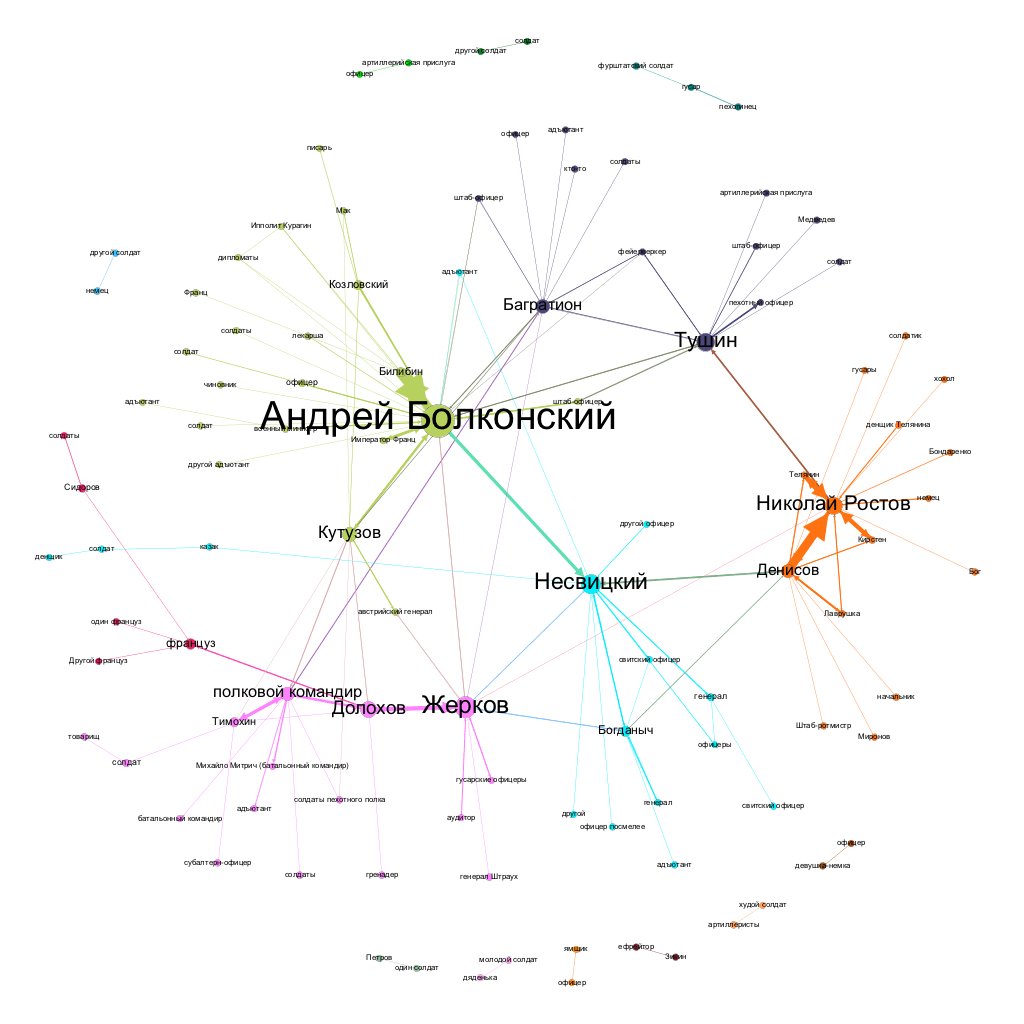

1. Dialogic communication network in War and Peace:

- 566 identified speakers (nodes)

- 6500 speeches →

1141 connections (edges) - Edge weights: number of speeches from char. A to char. B

- Directed network (weight of the 'Andrei → Natasha' edge is not the same as the weight of 'Natasha → Andrei')

Comparing top characters by different centralities

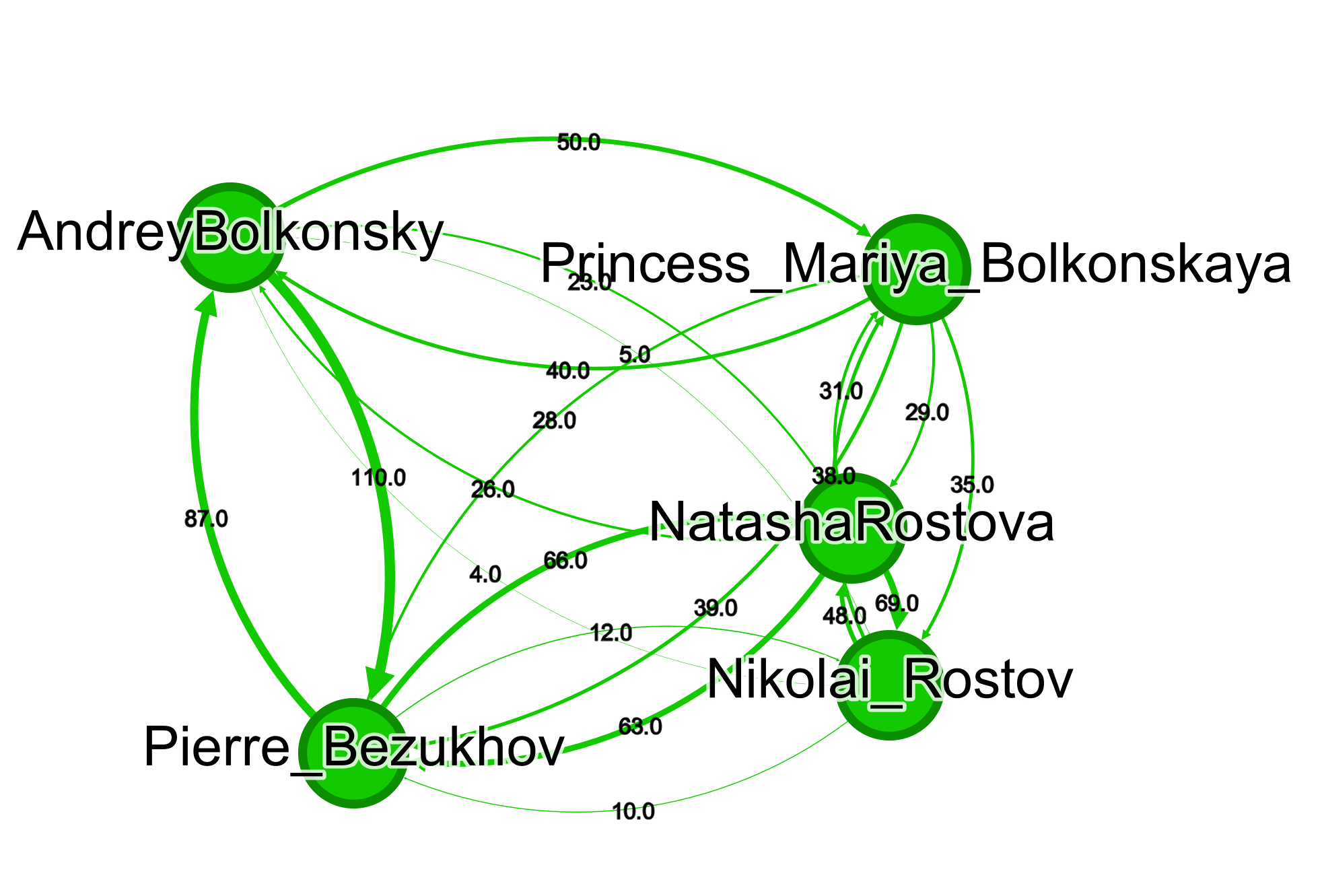

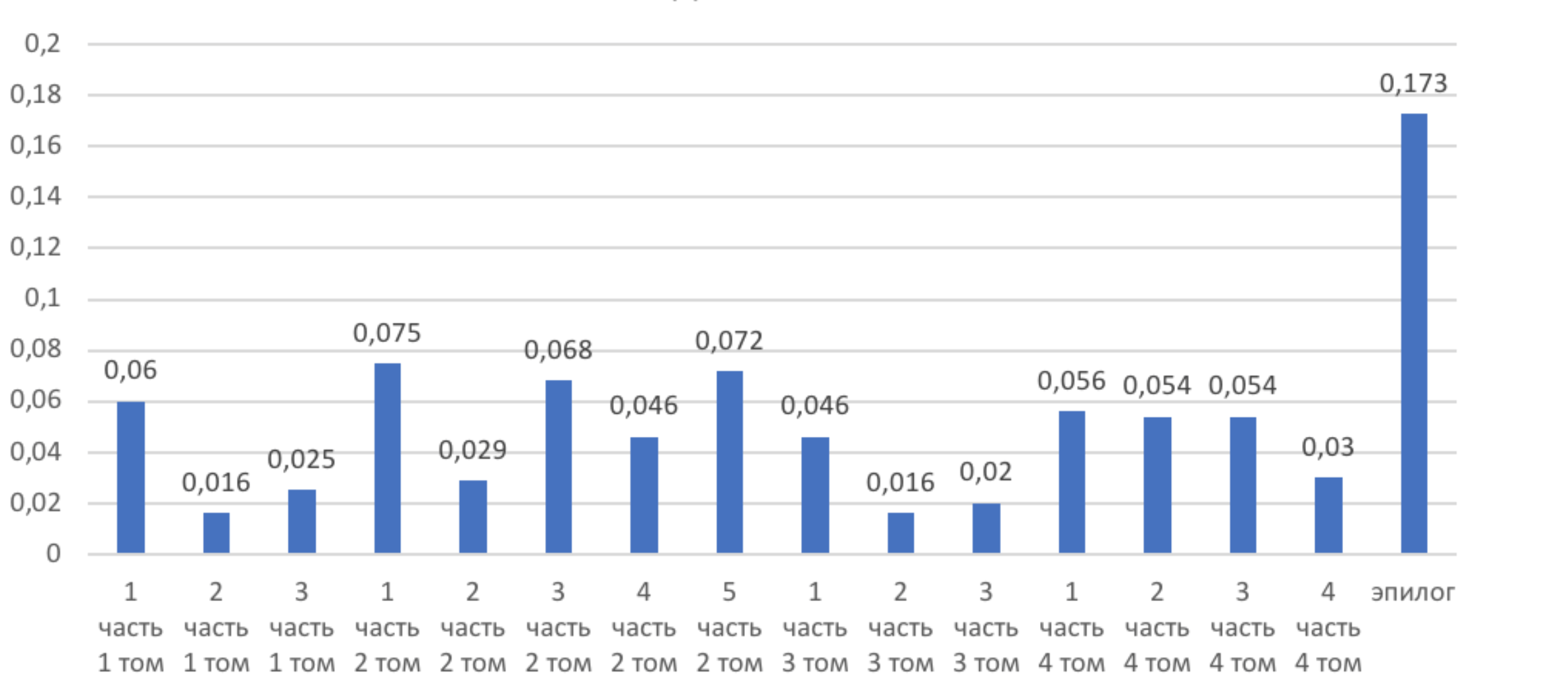

Dynamic sub-networks by parts (books) of the novel

War-time sub-networks are less dense than the peaceful ones:

1805 war events

1805 war events

1812 war events

1812 Borodino Battle

epilogue

Certain types of military characters are distinguishable by their betweenness-to-degree ratio

Book 2 network (Battle of Schöngrabern/Schlacht bei Hollabrunn und Schöngrabern)

In reading any of Shakespeare's dramas whatever, I was, from the very first, instantly convinced that he was lacking in the most important, if not the only, means of portraying characters: individuality of language, i.e., the style of speech of every person being natural to his character.

(Leo Tolstoy, A Critical Essay on Shakespeare,

trans. V. Tchertkoff)

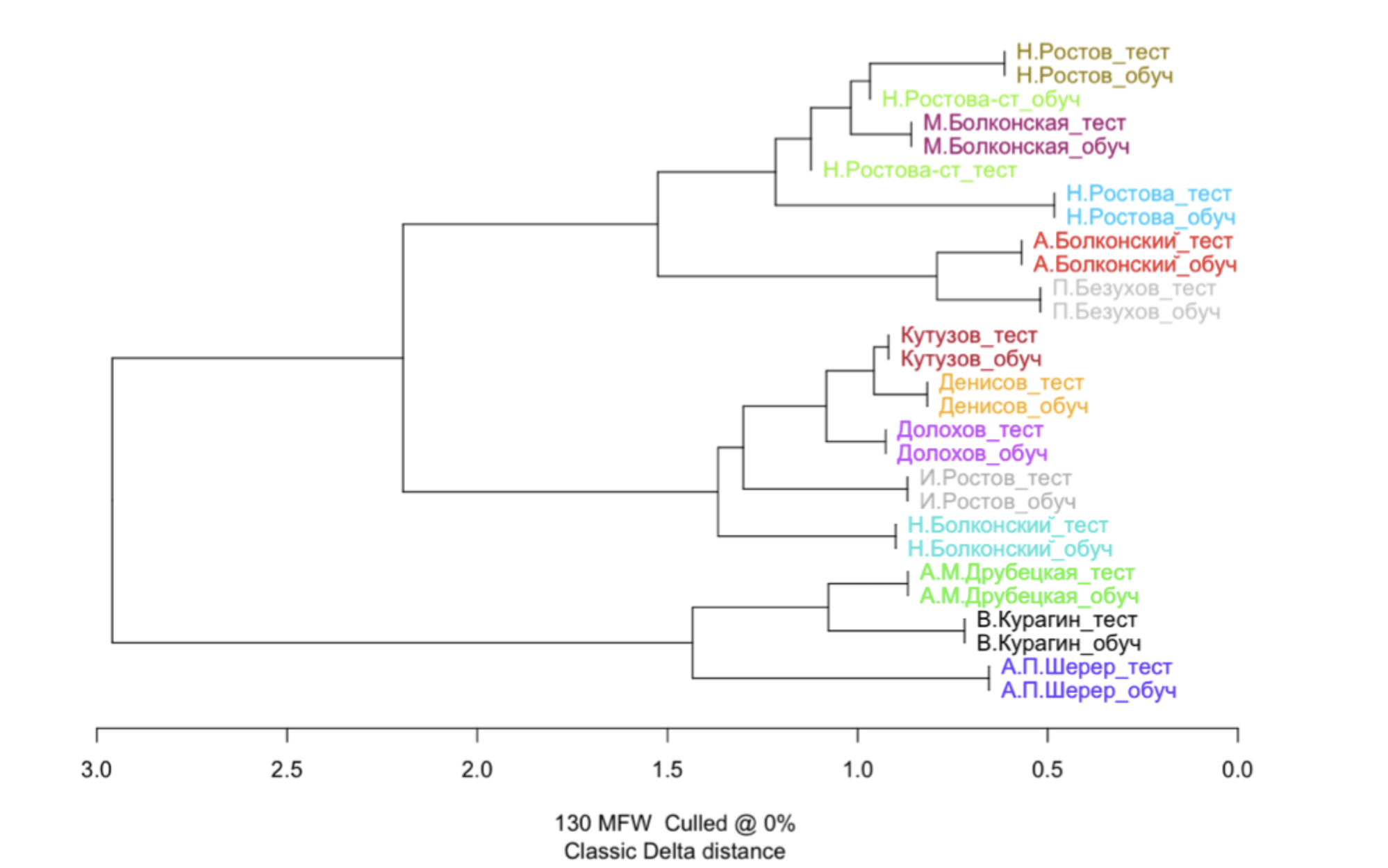

2. Character idiolects

Tolstoy himself on the importance of the individuality of character speech:

Do characters of War and Peace show speech individuality?

Stylometrically, it seems so

Though, to be fair, Shakespearean characters too:

But do Tolstoy's characters all speak in a natural way?

All his characters speak, not their own, but always one and the same Shakespearian, pretentious, and unnatural language, in which not only they could not speak, but in which no living man ever has spoken or does speak.

(Leo Tolstoy, A Critical Essay on Shakespeare,

trans. V. Tchertkoff)

Rostov family:

Соня! что ты?.. Что, что с тобой?

У-у-у!.. Сейчас, сейчас, не ходи, папа!

Ничего, маменька, право, ничего, так

Что? Кому?.. Шутишь!

Николушка... письмо... ранен... бы... был... ma chère... ранен... голубчик мой... графинюшка... в офицеры произведен... слава богу... Графинюшке как сказать?..

Пе... Петя... Поди, поди, она... она... зовет.. Я, я... я поеду с вами!

Видела? Видела? Что видела?

I'm not so sure... you do not have to know Russian to see the difference:

Prince Vassily Kuragin

Я думаю,— сказал князь, улыбаясь,— что, ежели бы вас послали вместо нашего милого Винценгероде, вы бы взяли приступом согласие прусского короля. Вы так красноречивы. Вы дадите мне чаю?

Я спрашиваю у тебя, когда ты получил письмо от Болконского

Ежели бы знали, что вы этого хотите, праздник бы отменили

Помните, что вы будете отвечать за все последствия,— строго сказал князь Василий,— вы не знаете, что вы делаете.

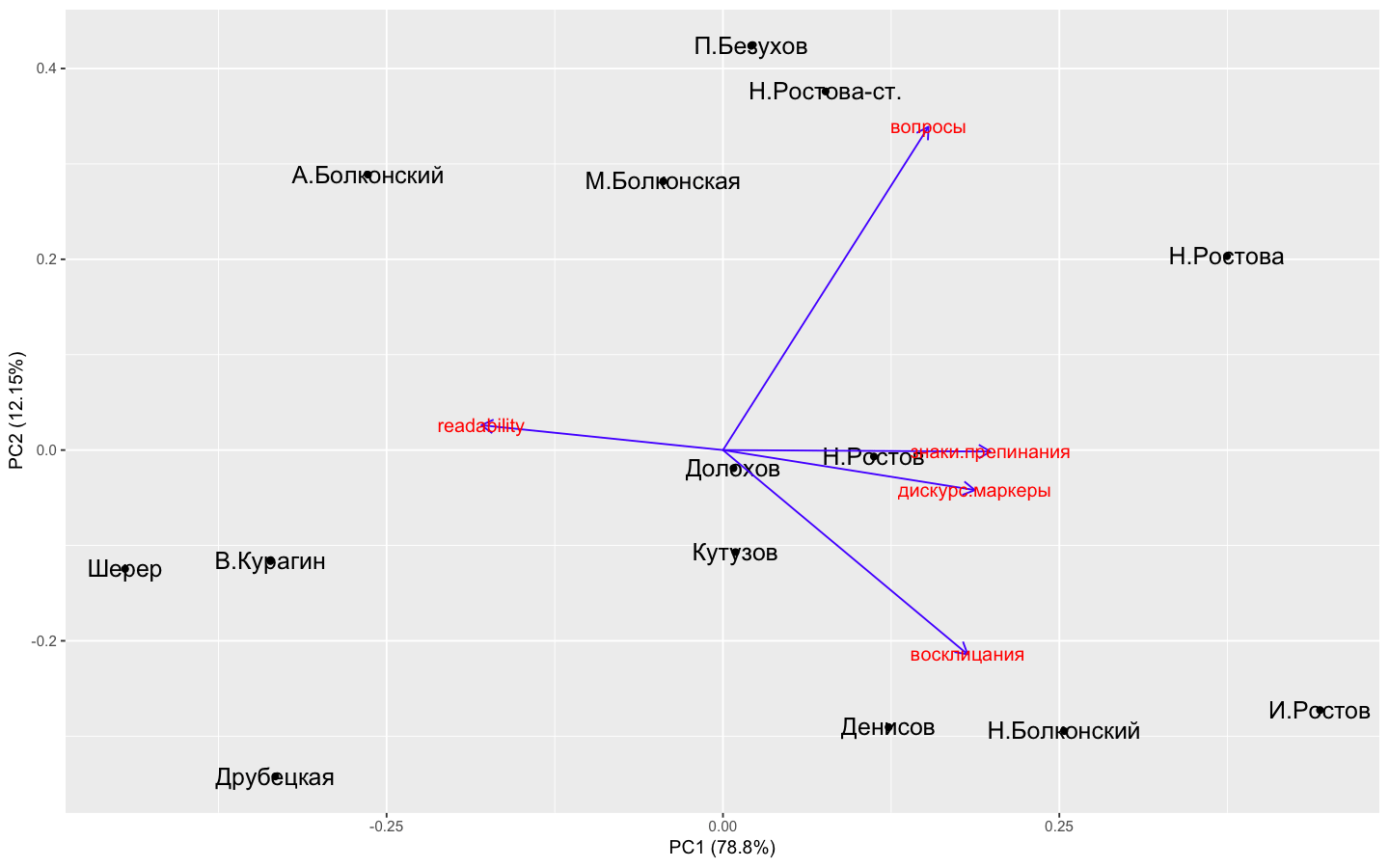

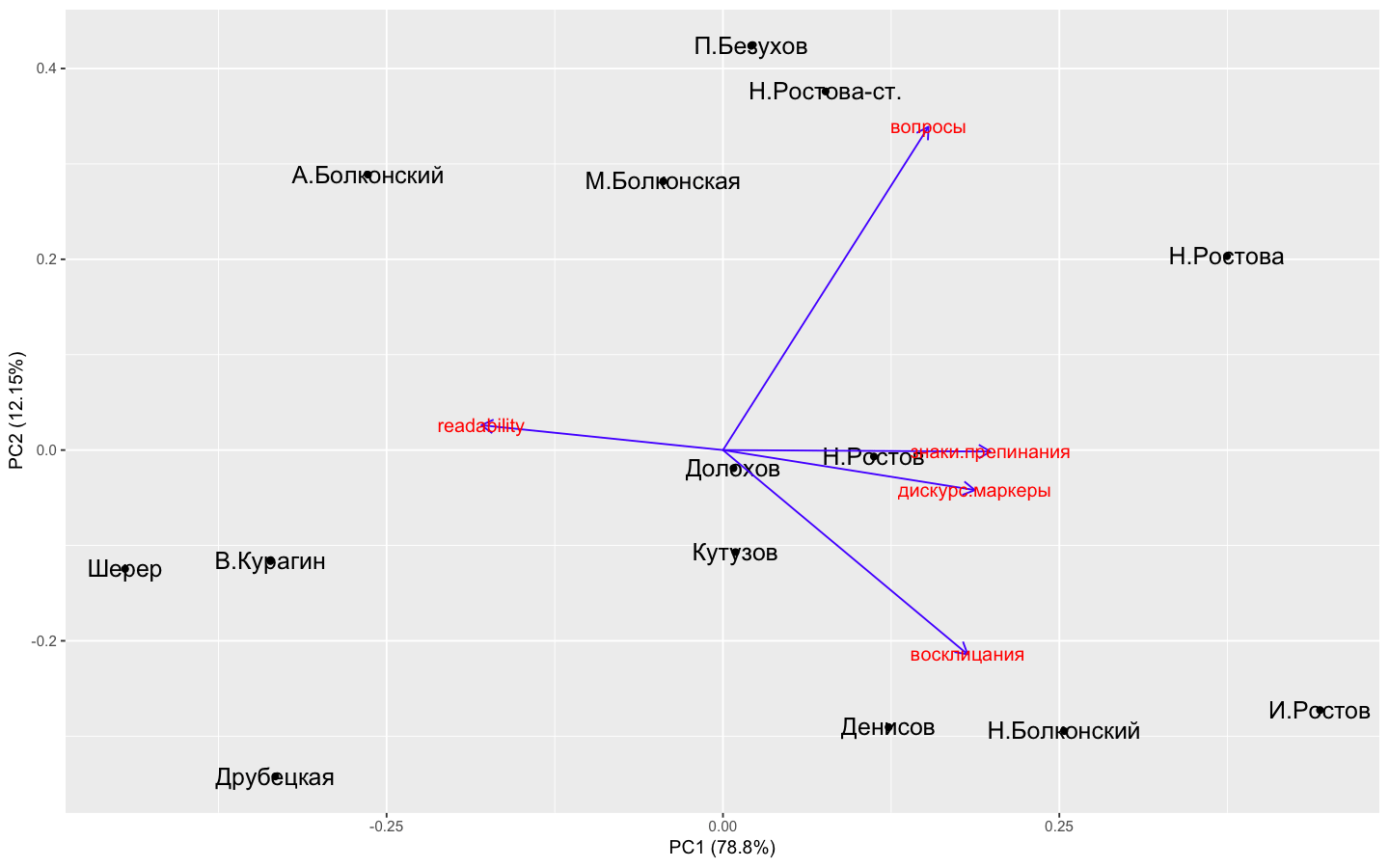

Can we try to measure that?

A simplistic 5-dimensional model:

- Share of exclamatory (!) statements

- Share of question (?) statements

- Share of punctuation (!"#$%&\'()*+,-./:;<=>?@[\\]^_`{|}~)

- Share of discourse markers (interjections, gramm.particles)

- Readability score (combined)

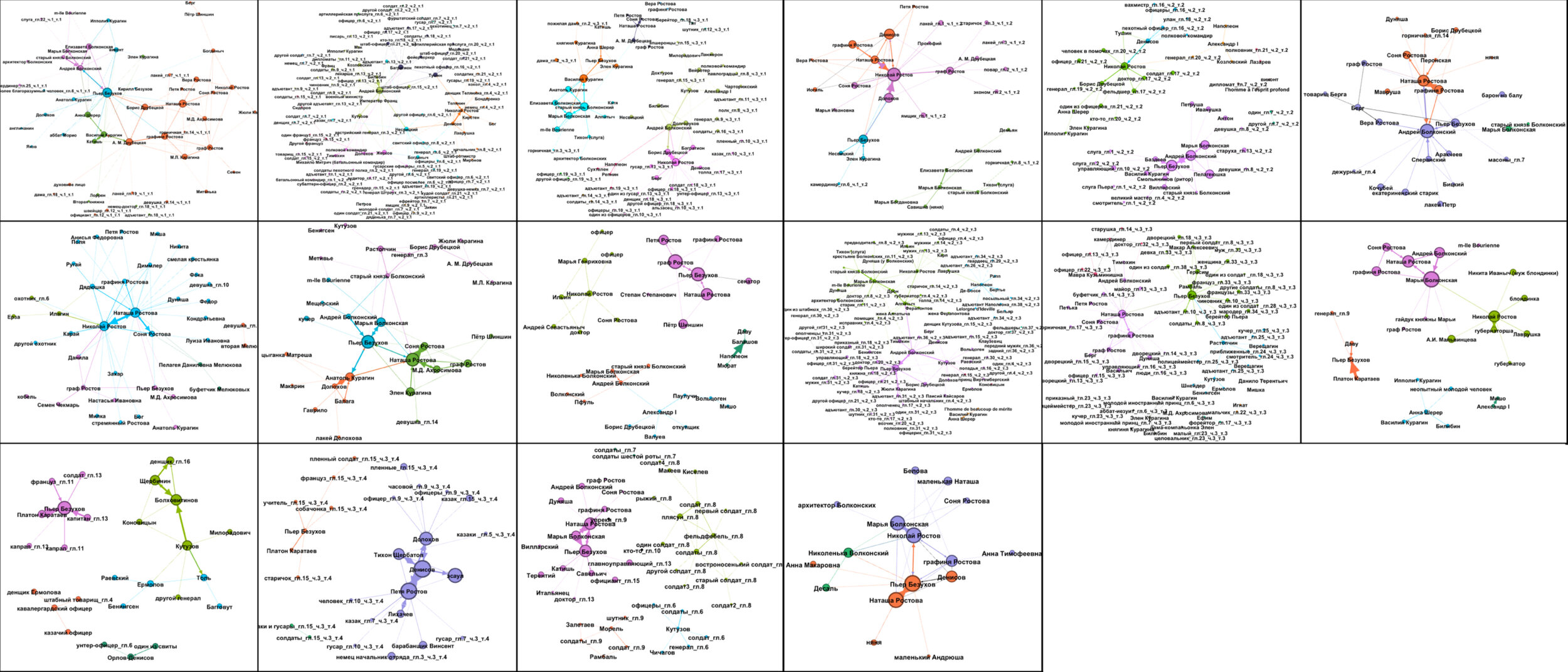

Quantitative analysis of character speeches

2. Characters in this 5-dimensional model:

A.Sherer

V.Kuragin

A.Drubetskaya

Andrei Bolkonsky

Mariya Bolkonskaya

Pierre Bezukhov

N. Rostova (Natasha's & Nikolai's Mother)

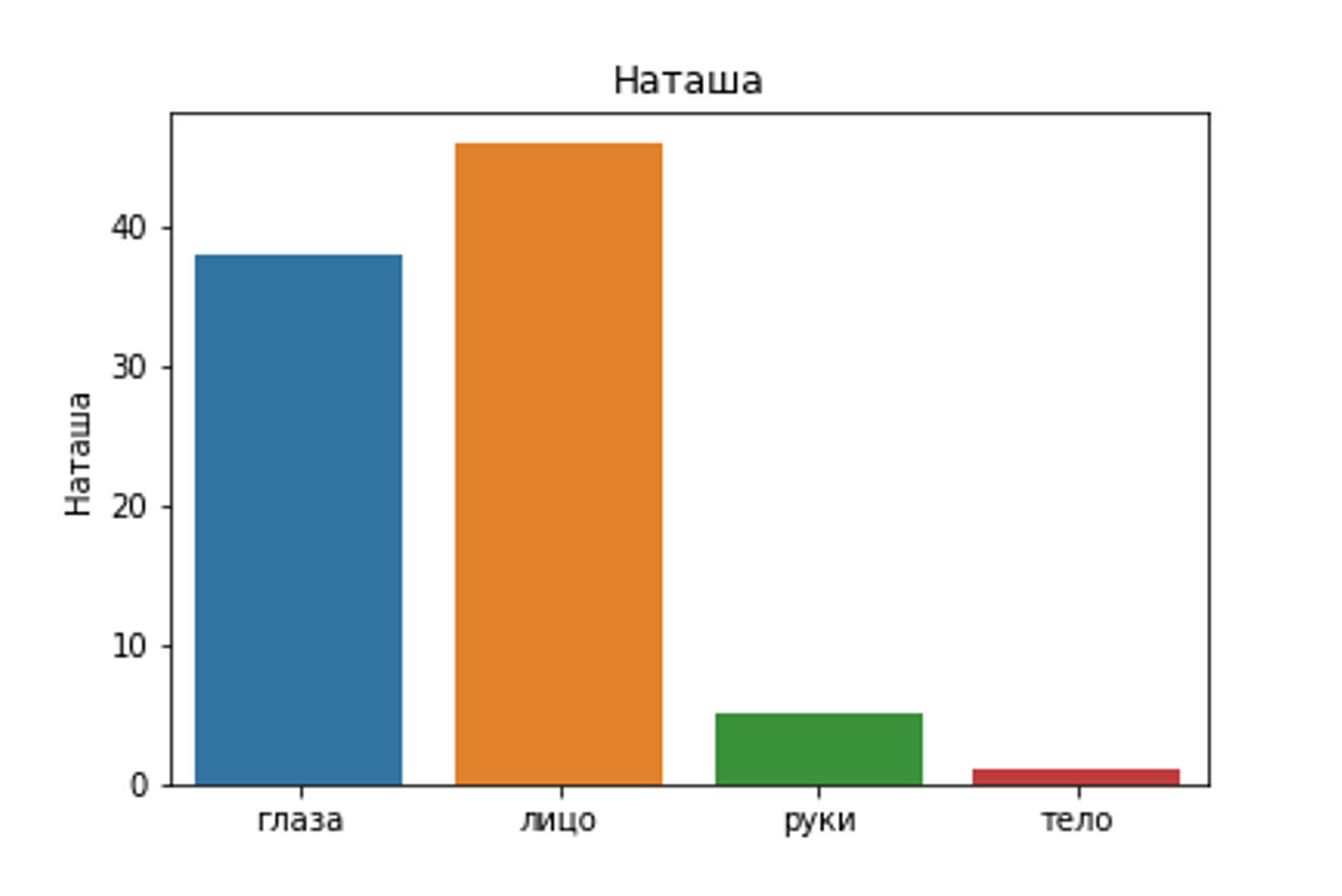

Natasha Rostova

Ilya Rostov (Natasha's & Nikolai's father)

Nikolai Rostov

Nikolai Rostov

Dolokhov

Kutuzov

Denisov

Nikolai Bolkonsky (Mariya and Andrei's father)

2. Characters in this 5-dimensional model:

A.Sherer

V.Kuragin

A.Drubetskaya

Andrei Bolkonsky

Mariya Bolkonskaya

Pierre Bezukhov

N. Rostova (Natasha's & Nikolai's Mother)

Natasha Rostova

Ilya Rostov (Natasha's & Nikolai's father)

Nikolai Rostov

Nikolai Rostov

Dolokhov

Kutuzov

Denisov

Nikolai Bolkonsky (Mariya and Andrei's father)

Highly exclamatory, informal speech

Highly readable formal speech

Questioning characters

- Her maternal instinct told her that Natasha had too much of something, and that because of this she would not be happy. (War and Peace, Natasha's mother fearing Natasha's upcoming marriage with Andrei Bolkonsky)

- "What did Nicholas' smile mean when he said 'chosen already'? Is he glad of it or not? It is as if he thought my Bolkonsky would not approve of or understand our gaiety" (War and Peace, Natasha's train of thought around the same time)

The distance between the Rostov family and Andrei Bolkonsky

Prince Andrei's speech, in contrast to most other characters, has only as much irregularity as is necessary to express inner agitation. [...] The rationalistic principle, which forms the core of the spiritual culture of the Bolkonskys—father and son—and which is so characteristic of certain progressive movements of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, could not tolerate the chaos of emotions that push speech far beyond the boundaries of logical form. Strict logic characterizes the syntax, vocabulary, and stylistic forms of the young Bolkonsky's statements.

(A. Saburov, War and Peace: Themes and Poetics, (1959), p. 550)

Traditional literary scholarship on Andrei's speech

[T]he distinctiveness of Natasha's speech lies not so much in the linguistic material of her words as in the manifestations of her temperament. Her speech is constructed not on logical or grammatical principles but on expression. Her first [...] and last [...] remarks are, in essence, marked by the same fragmentariness. Natasha often names a phenomenon while leaving the judgment unfinished. Her speech is emotional and vivid.

(A. Saburov, War and Peace: Themes and Poetics, (1959), p. 566)

Traditional literary scholarship on Natasha's speech

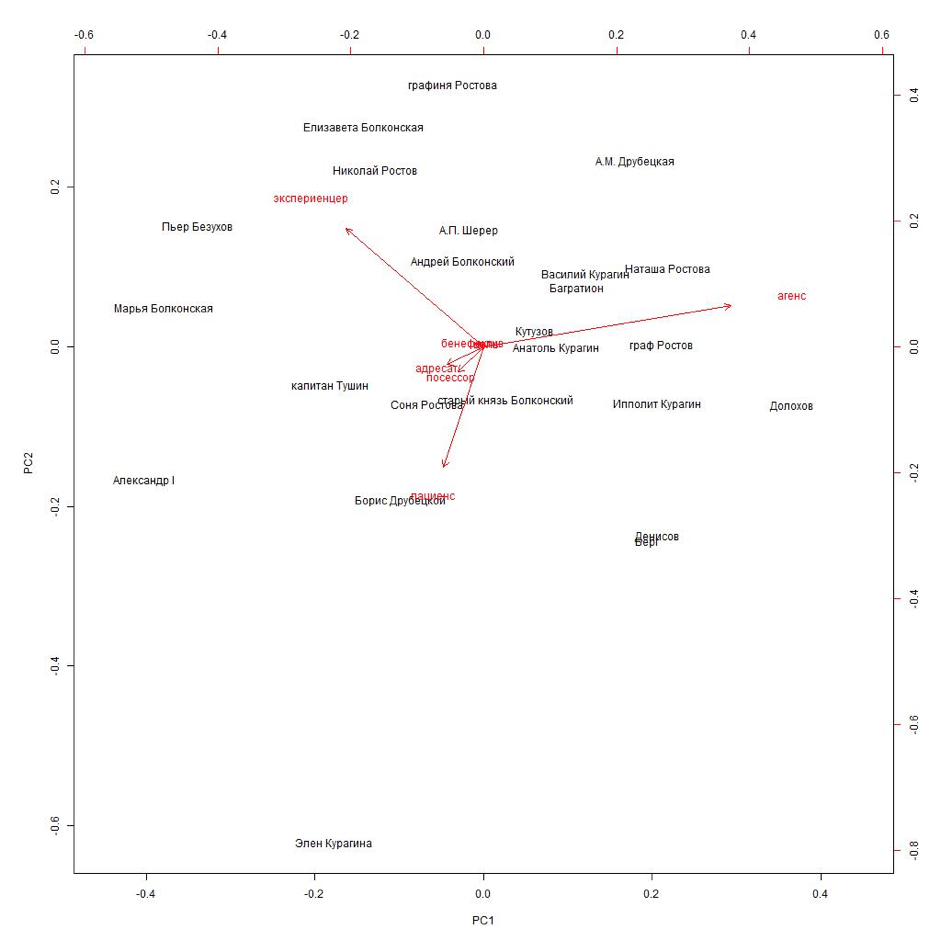

3. Semantic roles: 'objectivized' and 'experiential' characters

'Object' characters

'Agentive' characters

'Experiential' characters

Pierre Bezukhov

Mariya Bolkonskaya

Helene Kuragina

Natasha Rostova

A.M. Drubetskaya

Boris Drubetskoy

Dolokhov

Denisov

Berg

Alexander I

N. Rostova (Natasha's & Nikolai's Mother)

Nikolai Rostov

Elizaveta Bolkonskaya

Andrei Bolkonsky

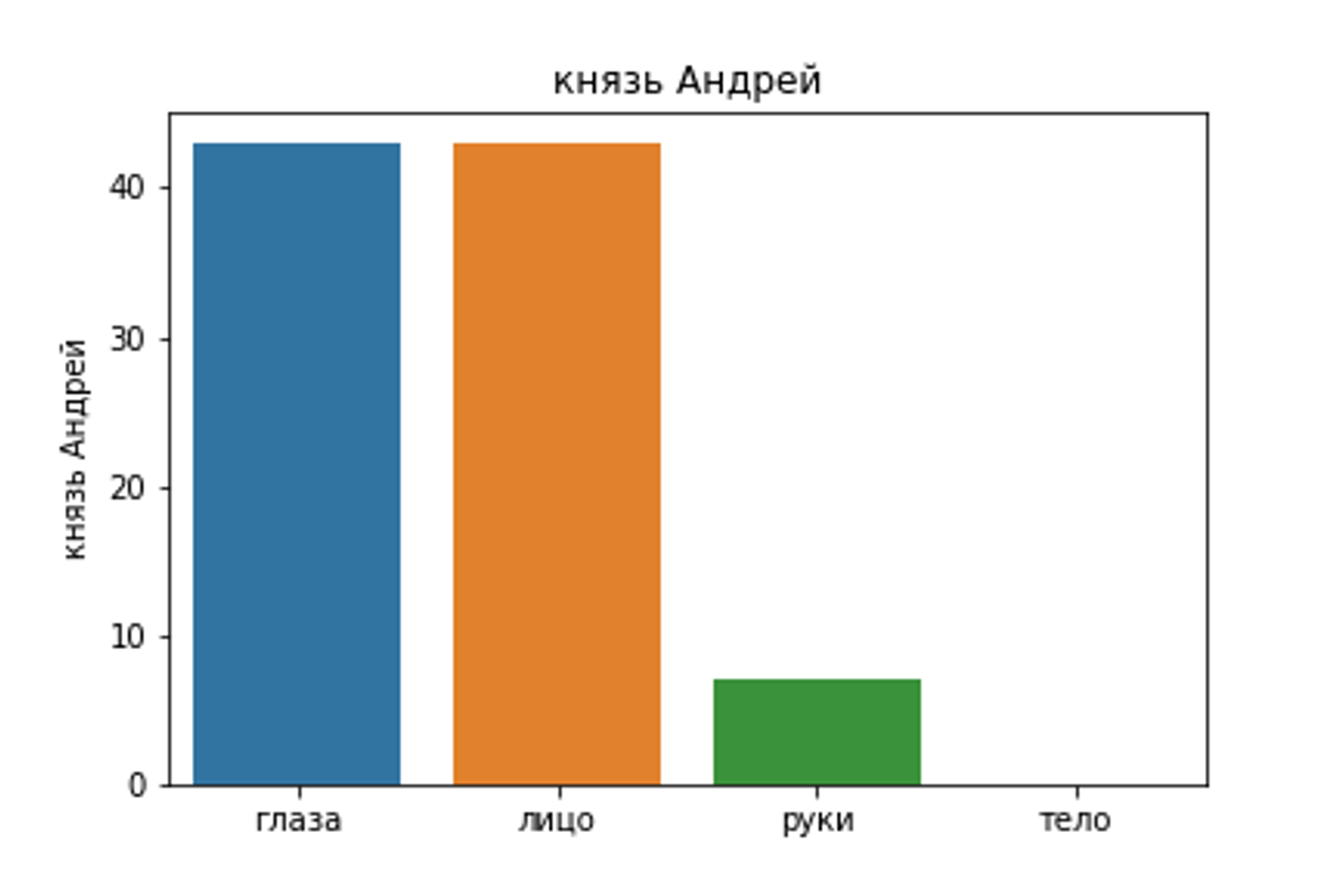

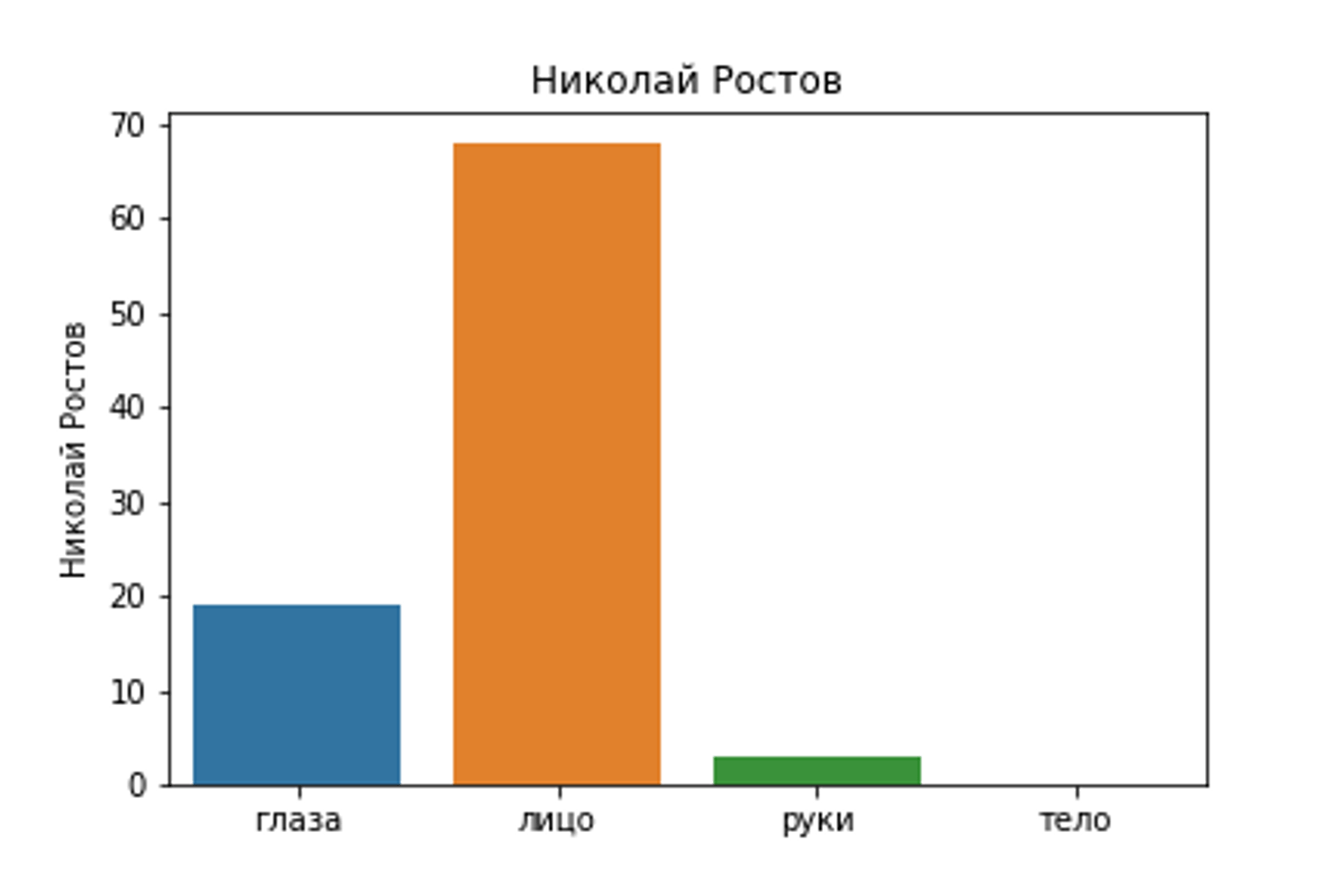

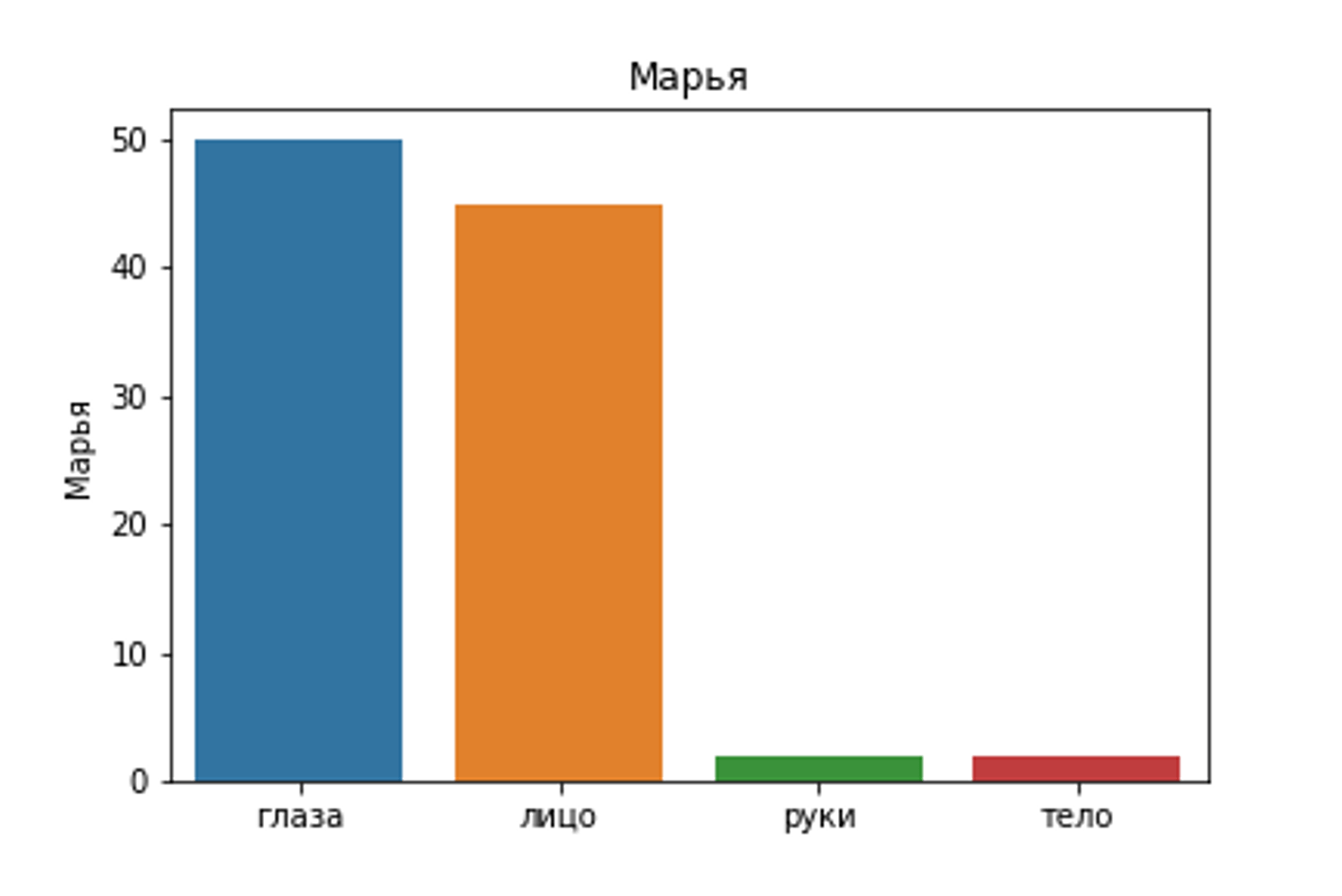

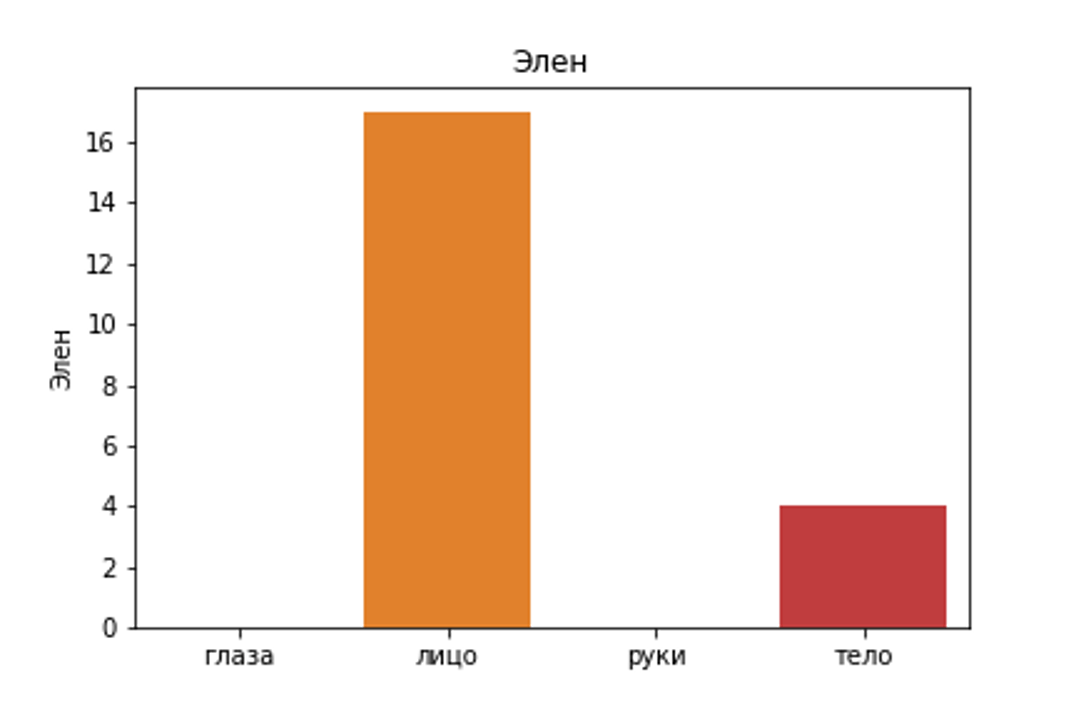

The complete antagonist to Marya is Hélène, whose portrait never includes descriptions of her eyes and hands. Her face and body make up only 19% of her portrait descriptions. Hélène’s portrait is created using entirely different nouns—primarily shoulders (38%), chest and bust (17%), head (8%), neck (8%), and waist (4%).

Bonch-Osmolovskaya, A. (2016)

Check this juxtaposition of Helene and other characters according to portrait features:

Check this juxtaposition of Helene and other characters according to portrait features:

eyes

eyes

eyes

eyes

eyes

face

face

face

face

face

hands

hands

hands

hands

hands

body

body

body

body

body

Mariya Bolkonskaya

Helene Kuragina

Natasha Rostova

Nikolai Rostov

Andrei Bolkonsky

vs

Takeaways

-

The study of characters represents an excellent bridge between literary studies and computational methods

-

One one hand, characters are tangible, palpable, identifiable units of text (unlike e.g. plot, themes, or style)

-

On the other hand, characters are literary entities, not just 'facts of language' (like words, phrases, and other linguistic units)

Thank you!

-

Baldick, C. (2008). Character. In The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms. Oxford University Press.

-

Bonch-Osmolovskaya, A. "Corpus Observations on the Portraits of Characters in "War and Peace"". Leo Philologiae: Festschrift in Honor of the 70th Birthday of Lev Sobolev. Moscow: Buky-Vedi, 2016, 13–51.

-

Bonch-Osmolovskaya A., & Skorinkin D. (2017). Text mining War and Peace: Automatic extraction of character traits from literary pieces. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities 32, 1, 17–24.

-

Bonch-Osmolovskaya, A., Skorinkin, D., Pavlova, I., Kolbasov, M., Orekhov, B. (2019). Tolstoy semanticized: Constructing a digital edition for knowledge discovery. Journal of Web Semantics 59, 100483.

-

Bullard, J., & Alm, C. O. (2014). Computational analysis to explore authors’ depiction of characters. In Proceedings of the 3rd Workshop on Computational Linguistics for Literature (CLFL).

-

Ciotti, F. (2016). Toward a formal ontology for narrative. Matlit: Materialidades Da Literatura, 4(1), 29–44.

-

Giovannini, L. (2025). Evolutive Dynamics in Early Modern European Drama: A Computational Perspective. Doctoral dissertation, University of Potsdam/University of Padua, to appear.

References

-

Grayson, S., Mulvany, M., Wade, K., Meaney, G., & Greene, D. (2016). Novel2vec: Characterising 19th century fiction via word embeddings.Proceedings, 24th Irish Conference on AI and Cognitive Science.

-

Hartner, M. (2024). Fictional characters in literary theory — A short history. e-Rea, 21(2).

-

Jannidis, F. (2019). Character. In Hühn, P., et al. (Eds.), The Living Handbook of Narratology. Hamburg University.

-

Rinehart, H. (2000). Aristotle’s four aims for dramatic character and his method in the Poetics. University of Toronto Quarterly, 69(2), 529–539.

-

Piper, A. (2019). Enumerations: Data and Literary Study. University of Chicago Press.

-

Skorinkin, D. (2022). Characters of L. N. Tolstoy's War and Peace: occurrences in the text, direct speech and semantic roles". Open Data Repository on Russian Literature and Folklore, v1.

-

Yoder, M., Khosla, S., Shen, Q., Naik, A., Jin, H., Muralidharan, H., & Rosé, C. (2021). FanfictionNLP: A text processing pipeline for fanfiction. ACL Proceedings of the Third Workshop on Narrative Understanding, 13-23.